Written by: Daniella Marie Ohnemus (MS-3, NUFSOM); Edited by: Michael Macias, MD (EM Resident Physician, PGY-4, NUEM); Expert Commentary by: Daniel Ganger, MD

Introduction

Over 600,000 adults in the United States have liver cirrhosis, and as many as 30 to 45 percent of these patients will develop overt neuropsychiatric abnormalities [1,2]. Those who do develop these cognitive problems have a poor prognosis, with a three-year survival of only 23 percent [3].

These behavioral abnormalities fall on a spectrum of what is known as hepatic encephalopathy (HE), an umbrella term for the neuropsychiatric changes associated with portal-systemic shunting. As blood begins to bypass the cirrhotic liver via venous collaterals, toxic metabolites that should have been cleared by the liver begin building up in the bloodstream. Ultimately, this accumulation can lead to a range of problems with cognitive and executive function. Sometimes these problems are subtle and difficult to spot – slight alterations to the patient’s short-term memory or ability to concentrate. In more extreme cases, HE can manifest as extreme confusion, stupor, and even coma.

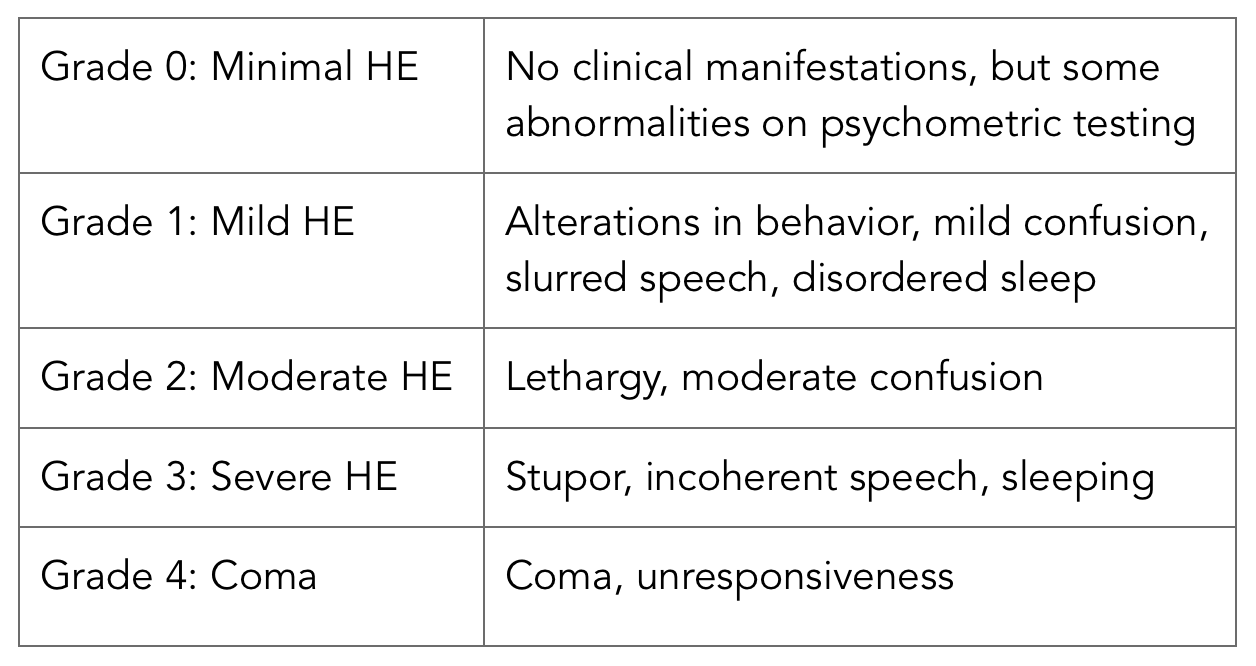

To more accurately describe the severity of HE, the West Haven Grading System is used (table seen to the right).

While the pathophysiology of HE boils down to portal-systemic shunting, there are several factors that can precipitate an episode [4].

These include:

- GI bleed

- Infection

- Metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemia

- Renal failure, azotemia

- Increased dietary protein

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Drugs or sedatives

HE in the ED

History & Physical

The West Haven Grading System is especially useful for triaging patients in the ED, where problems must be identified quickly and more involved psychometric testing would be impractical. In addition to screening for recent changes in alertness, attention span, memory, the following components of a history and physical may be useful in identifying HE in the emergency department setting [4,5,6]:

- A thorough review of the patient’s medication list to identify any new medications that could explain the change in the patient’s mental status or trigger acute HE

- Obtaining collateral information from a family or friend who can provide a more accurate timeline of symptoms and any behavior changes

- Assessing for changes in sleep patterns, especially reversal of the sleep-wake cycle

- Evaluations of Attention

- Serial 7s test: Having the patient count up by 7s, or down from 100 by 7s

- “A” deletion test: Ask the patient to delete or identify all of the letter A’s in a paragraph of text in a 1 to 2-minute period. Then, calculate the number of A’s that were missed.

- Fetor hepaticus

- Portal-systemic shunting can allow thiols to pass directly into the lungs, leading to foul-smelling breath.

- Neuromotor abnormalities

- Tremor

- Increased deep tendon reflexes

- Babinski sign

- Asterixis (flapping of outstretched, dorsiflexed hands)

Work-up

In the emergency department, a thorough investigation to search for both a possible trigger of HE as well as for an alternative explanation of the patient’s symptoms should be undertaken. While a majority of this will be picked up on history, imaging and laboratory testing may prove useful. This may include:

- Lab - CBC, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, ammonia, pH, and hepatic function tests

- Blood ammonia levels may be used in conjunction with a thorough history and physical, but elevated ammonia alone is not enough to treat or diagnose HE.

- CT - Can help exclude cerebral hemorrhage or other lesions

- CXR - To identify pneumonia, which may be a precipitating cause. Infections are the major precipitant of HE.

- Diagnostic paracentesis - To identify spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

- Urinalysis

Management

In the ED, treatment should focus initially on intravenous hydration and correction of any hypoglycemia or electrolyte disturbance. Blood ammonia lowering therapy should then be initiated with either non absorbable di-saccharides or oral antibiotics. Correction of any precipitating cause of HE should also be addressed.

The disposition of these patients depends on grade and severity (Refer to table above). Patients with grade III or IV must be admitted and may require airway management in the emergency department as well as ICU monitoring given their severely depressed mental status. Those with grade II HE may also require admission if they are not able to adhere to treatment or do not have a caretaker who can carefully observe them for worsening symptoms [7]. For patients that will be sent home, it is of upmost importance to establish a discharge plan, including both treatment and close follow up with their gastroenterologist or hepatologist.

The core components of treatment for HE include [7, 8]:

Take Home Points

Diagnosing HE in the ED requires a thorough history and physical that should incorporate quick screening tests for cognitive function and neuromotor abnormalities

Laboratory evaluation and diagnostic imaging play an important role in both ruling out alternative causes of altered mental status and identifying the precipitating cause of an episode of HE. Infection is the most common precipitating cause.

Treatment of HE has three main components: providing supportive care, addressing and correcting precipitating causes, and initiating ammonia-lowering therapy.

The West Haven Grading System, along with evaluation of the patient’s reliability and social situation, can help establish the patient’s disposition.

Expert Commentary

This is an excellent review and guide of do’s and don’ts to patients who present to the ED with mental status changes and highly suspicious to have hepatic encephalopathy (HE) . In addition to the Take Home Points, here are my comments.

- West Haven Classification: easy to use and document. Counting number of asterixis flaps over 30 seconds allows to follow this parameter more objectively. HE patients in stages 2, 3 and 4 will be coming to the ED and gettinga history of fall or trauma should trigger an immediate order to image the brain and exclude an intracranial bleed. These patients are at risk to bleed as they have coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia associated with their advanced liver disease and some may be even taking blood thinners (i.e. indicated at times when they have known portal vein thrombosis).

- Grade 3 and 4 HE with high levels of ammonia ( >150 ), should also trigger imaging of the brain to exclude brain edema , which is more often seen in acute liver failure but may also be seen in cases of acute on chronic liver failure ( with known liver disease).

- Patients who present with ascites should always have a diagnostic tap to exclude SBP, a known precipitant of HE. Recent increasein diuretic therapy should also be considered as triggerof HE associated with electrolyte imbalance and volume depletion.

- Some patients who present with liver disease and mental status changes do not have HE , but are over-sedated( intentionally or accidentally). Drug screen is always indicated when a patient without previously known liver disease presents with mental status changes.

- Placing a nasogastric tube to exclude GI bleeding, another known precipitant of HE, should not be deferred for fear of presence of varices.

- Grade 3 and 4 HE patients should be intubated to protect airway and prevent aspiration.

Daniel R.Ganger, M.D. FACP AGAF FAASLD

Transplant Hepatology; Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery; Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Other Posts You May Enjoy

How to cite this blog post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ohnemus D, Macias M (2017, February 28). Hepatic Encephalopathy In The ED [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary By Ganger D]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hepatic-encephalopathy

References

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes G, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazon R, Luke A, Volk ML. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: A population-based study. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2015; 49(8): 690-6.

- Poordad FF. Review article: the burden of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25(1): 3-9.

- Bustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura PJ, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1999; 30: 890-5.

- Khalili M, Burman B. Liver Disease. In: Hammer GD, McPhee SJ. eds. Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine, Seventh Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy in adults: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Runyon B (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA.

- Greenberger NJ. Portal Systemic Encephalopathy & Hepatic Encephalopathy. In: Greenberger NJ, Blumberg RS, Burakoff R. eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Gastroenterology, Hepatology, & Endoscopy, 3e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy in adults: Treatment. In: UpToDate, Runyon B (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA.

- Bleibel W, Al-Osaimi AMS. Hepatic Encephalopathy. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(5): 301-309.

- AASLD and EASL Guidelines on hepatic encephalopathy. www.AASLD.org/practice guidelines. www.EASL.org