Written by: Jonathan Hung, MD (NUEM ‘21) Edited by: Jon Anderek (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Andrew Moore, MD, MS

Introduction

Syncope is defined as a brief loss of consciousness that is self-limited. [1] It is a commonly seen chief complaint in the emergency department (ED), consisting of up to 3% of ED visits. [2] There are both benign causes of syncope such as vasovagal syncope and more serious causes such as arrhythmias. By the time these patients present to the ED, they are often asymptomatic and hemodynamically stable. Part of the ED workup and disposition includes risk stratification of these patients that can vary by provider and hospital system. [3] For those who present with high-risk features, ED physicians often recommend admission to the hospital for telemetry monitoring and expedited evaluation with echocardiography. [4] Multiple decision rules, most notably the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR), have been developed to identify syncope patients at risk for poor outcomes. The SFSR takes into account predictors such as a history of heart failure, an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG), and hypotension to determine 7-day negative outcomes for patients presenting to the ED with syncope. [5] Another study called the Osservatorio Epidemiologico sulla Sincope nel Lazio (OESIL) includes age over 65 and syncope without prodrome in addition to a history of cardiovascular disease as part of their decision-making tool. [6] Lastly, the Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department (ROSE) also takes lab results such as brain natriuretic peptide and hemoglobin into account. [7] Despite the numerous studies examining risk stratification in syncope, each one has limitations and ultimately lack adequate sensitivity and specificity for widespread clinical adoption. A new study published in Academic Emergency Medicine is one of the largest studies to develop a risk tool that identifies adult syncope patients at 30-day risk for serious adverse outcomes defined as a serious arrhythmia, need for intervention to correct arrhythmia, or death. [8]

Study

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Predicting Short-term Risk of Arrhythmia among Patients With Syncope: The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score. Baumann BM, ed. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1315-1326.

Study Design

Multi-center, prospective, observational cohort study.

This was a derivation study used to define the parameters of the risk score.

Population

Inclusion criteria:

Syncope patients presenting within 24 hours of the event

Adults age ≥16

Exclusion criteria:

Prolonged loss of consciousness

Change in mental status from baseline

Witnessed seizure

Head trauma or other trauma requiring admission

Unable to provide history due to alcohol intoxication, illicit drug use or language barrier

Obvious arrhythmia or nonarrhythmic serious condition on presentation

Intervention protocol

ED physicians and emergency medicine residents were trained to assess standardized variables at the initial ED visit including time and date of syncope, event characteristics, personal and family history of cardiovascular disease, and final ED diagnosis. Other variables were obtained through chart review and included age, sex, vital signs, laboratory results and ECG variables. All ECGs were reviewed by a cardiologist, and abnormal variables were reviewed by a second cardiologist. Physician gestalt for dangerous etiology was also recorded for each patient. Multivariable logistic regression was used for the analysis.

Outcome Measures

Composite of death, arrhythmia, or procedural interventions to treat arrhythmias within 30 days of ED disposition

Results

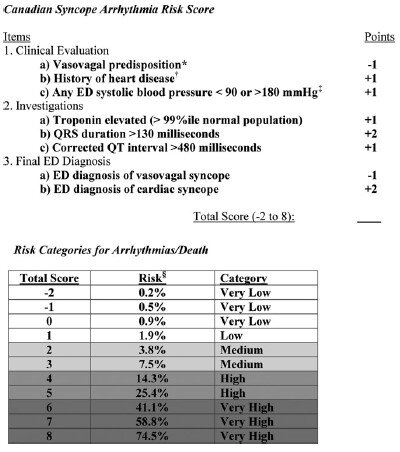

5,010 patients were enrolled in the study with 106 (2.1%) patients suffering arrhythmia or death within 30 days of ED presentation. Forty-five of the 106 patients suffered their adverse event outside of the hospital. The mean age of the study population was 53.4 (SD 23.0 years) and 54.8% were females. A total of 8 variables were included in the final model:

Vasovagal predisposition

History of heart disease (CAD, atrial fibrillation/flutter, CHF, valvular abnormalities)

Systolic blood pressure <90 or >180 mm Hg at any point

Troponin elevation

QRS duration >130 msec

QTc interval > 480 msec

ED diagnosis of cardiac syncope

ED diagnosis of vasovagal syncope

The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score had a sensitivity of 97.1% and specificity of 53.4% at a threshold score of 0 based on the study’s internal validation.

Interpretation

This study is the largest, multicenter study assessing predictors of short-term outcomes following initial ED presentation of syncope. The results are similar to previous studies that examined long-term outcomes. One interesting difference is that in prior studies, advanced age was a risk factor in arrhythmia or death, however it did not make the final model in this study. The strengths of this prospective study include the large patient population and that only 6.5% were lost to follow up. Furthermore, developing a simplified risk tool similar to the HEART score for chest pain, it can be easily utilized in the ED to help aid in decision making. Some limitations are that a large portion (54%) of patients did not have a troponin level measured and the study notes that these were usually younger patients with less comorbidities.

In practice, it may be difficult to use this tool if there is provider variation for when cardiac syncope is suspected and when a troponin level is measured. Whether or not the provider diagnoses vasovagal syncope or cardiac syncope is subjective as well, though may serve as a surrogate for “physician gestalt.” These results are helpful in risk stratifying syncope patients especially in regard to short-term outcomes, however this disease process is complex and cannot be oversimplified. Overall, this decision tool at the very least allows ED providers to have a shared decision-making conversation with more robust data to support the various options.

Take Home Points

The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score is a large, multicenter trial evaluating serious 30-day outcomes following an ED presentation for syncope

Emergency medicine physicians may consider using this tool to guide their clinical-decision making for syncope patients by offering risk percentages for 30-day adverse events

At the time this was written a validation study was underway

Expert Commentary

The management and disposition of syncope has been a conundrum for emergency physicians for decades. In fact, the last 20 years of syncope research have focused on development of a risk stratification score for the ED management of syncope. With the recent external validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Stratification Score [9] (CSRSS) and the recent publication of the FAINT Score [10] for syncope in older adults, we now have two prospectively derived studies to support risk stratification of the syncope patient. The external validation of the CSRSS showed good sensitivity for low risk patients with a sensitivity of 97.8%. None of the very low risk or low risk patients in the external validation died or suffered cardiac arrhythmia in 30 days. Based on this if your patient is very low risk or low risk you can safely discharge the patient home with primary care follow up.

In my practice, the CSRSS serves as an adjunct to clinician judgement. Using a risk stratification score is often the impetus for a shared decision-making discussion regarding risk and safe disposition. The results of the external validation study further support clinical use of the CSRSS.

The FAINT score also shows promise for risk stratification in older patients with syncope and near syncope. This score has not been externally validated, but focuses on the older population that many emergency physicians reflexively admit for cardiac monitoring.

Regardless of which decision score you decide to use in personal practice, most of these patients with unexplained syncope can be safely admitted for a short observation stay. It is safe to say that we have entered a golden age of syncope decision rules.

Andrew Moore, MD, MS

Emergency Physician and Emergency Care Researcher

Department of Emergency Medicine

Carilion Clinic

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Hung, J, Anderek, J. (2020, Sept 14). Canadian Syncope. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Moore, A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/canadian-syncope.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Brignole M, Moya A, de Lange FJ, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. European heart journal 2018;39:1883-948.

Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA, Jr. Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to U.S. emergency departments, 1992-2000. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:1029-34.

Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Gbedemah M, Richardson LD, Sun BC. National trends in resource utilization associated with ED visits for syncope. The American journal of emergency medicine 2015;33:998-1001.

Cook OG, Mukarram MA, Rahman OM, et al. Reasons for Hospitalization Among Emergency Department Patients With Syncope. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:1210-7.

Quinn JV, Stiell IG, McDermott DA, Sellers KL, Kohn MA, Wells GA. Derivation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with short-term serious outcomes. Annals of emergency medicine 2004;43:224-32.

Colivicchi F, Ammirati F, Melina D, Guido V, Imperoli G, Santini M. Development and prospective validation of a risk stratification system for patients with syncope in the emergency department: the OESIL risk score. European heart journal 2003;24:811-9.

Reed MJ, Newby DE, Coull AJ, Prescott RJ, Jacques KG, Gray AJ. The ROSE (risk stratification of syncope in the emergency department) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:713-21.

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne 2016;188:E289-98.

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. Multicenter Emergency Department Validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA internal medicine 2020;180:1-8.

Probst MA, Gibson T, Weiss RE, et al. Risk Stratification of Older Adults Who Present to the Emergency Department With Syncope: The FAINT Score. Annals of emergency medicine 2019.