An overview of Massive Transfusion Protocol

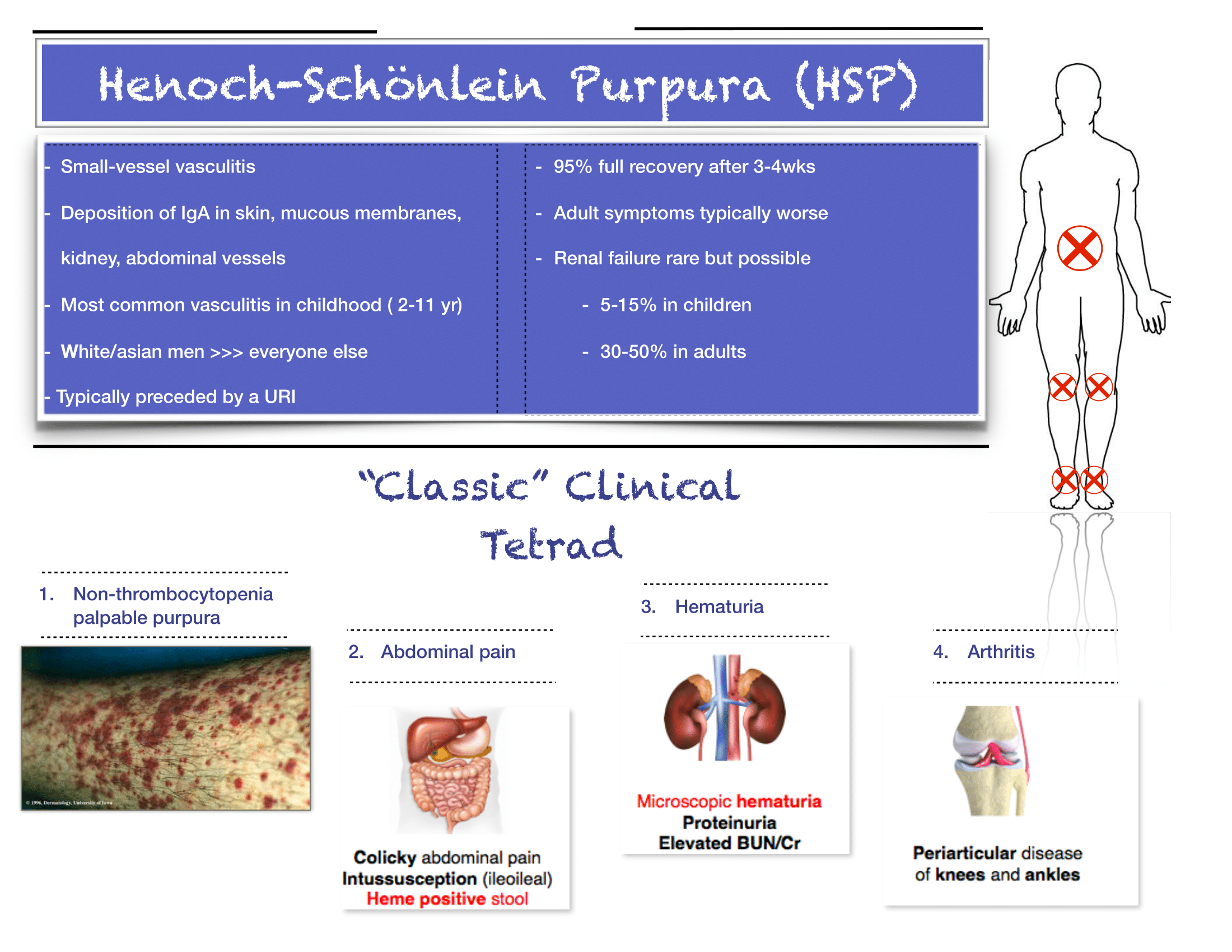

Henoch-Schonlein Purpura

Written by: Ben Kiesel, MD (NUEM PGY-1) Edited by: David Kaltman, MD (NUEM PGY-4) Expert Commentary by: Kirsten Loftus, MD, MEd

Expert Commentary

Thank you for providing this succinct review of HSP. This is not a diagnosis you will encounter frequently, but it’s an important one not to miss because, as you point out, there are several key implications for outpatient monitoring and follow-up. Here are a few additional tips when it comes to the diagnosis and initial management of HSP:

The diagnosis is truly a clinical one. If you have bilateral lower extremity petechiae/purpura plus belly pain, arthritis/arthralgia, or renal involvement, then you’ve made your diagnosis. Outside a urinalysis to evaluate for hematuria/proteinuria and checking a blood pressure to look for hypertension, there is limited utility for other diagnostic tests. Don’t forget to consult your favorite reference for normal pediatric blood pressure values to ensure you aren’t missing hypertension.

Renal disease is less common in kids compared to adults with HSP, but does happen. If you have hematuria/proteinuria or hypertension, go ahead and at least check a chemistry to look at BUN/Cr. Then talk with your favorite local pediatric nephrologist (if available) or PEM doc at your pediatric referral center to determine need for transfer versus close outpatient follow-up.

You appropriately point out that steroids are rarely indicated, and that hydration and NSAIDs will be your primary management. If you feel compelled to start steroids for severe abdominal pain (once you are sure it is not due to intussusception), you may need a longer (e.g. 4-8 week) taper, given the risk of rebound pain if tapered too quickly.

As always, set clear expectations with families and make sure they have good follow-up. I find that this can be a tough diagnosis to explain to parents, who are often quite scared about the rash. Spending some extra time talking with families once you’ve made the diagnosis can really go a long way. Warn parents that the rash is likely to persist for weeks and that the development of some additional petechiae/purpura is okay- you will prevent some unnecessary ED return visits this way. Strict return precautions for severe belly pain are key as HSP-associated intussuception is a very real complication. Every discharged patient should be seen by their PCP within about 1 week for a repeat UA and BP check- even if patients do not have evidence of renal disease at the time of diagnosis, it may develop later on, and close outpatient monitoring is critical.

Kirsten V. Loftus, MD, MEd

Attending Physician Emergency Medicine

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago

Instructor of Pediatrics (Emergency Medicine)

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

How to Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kiesel, B, Kaltman, D. (2020, May 18). Henoch-Schonlein Purpura. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Loftus, K]. Retrieved from https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hsp

Anticoagulation in Distal DVT

Anticoagulation in Distal DVT

Written by: William LaPlant, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: William Ford, MD (NUEM PGY-4) Expert commentary by: Kelsea Caruso, PharmD

Currently there is significant heterogeneity in the treatment of distal deep vein thromboses (DDVTs), which are DVTs that occur distal to the popliteal fossa. What is the best course of action when a reasonably healthy patient has a new calf DVT?

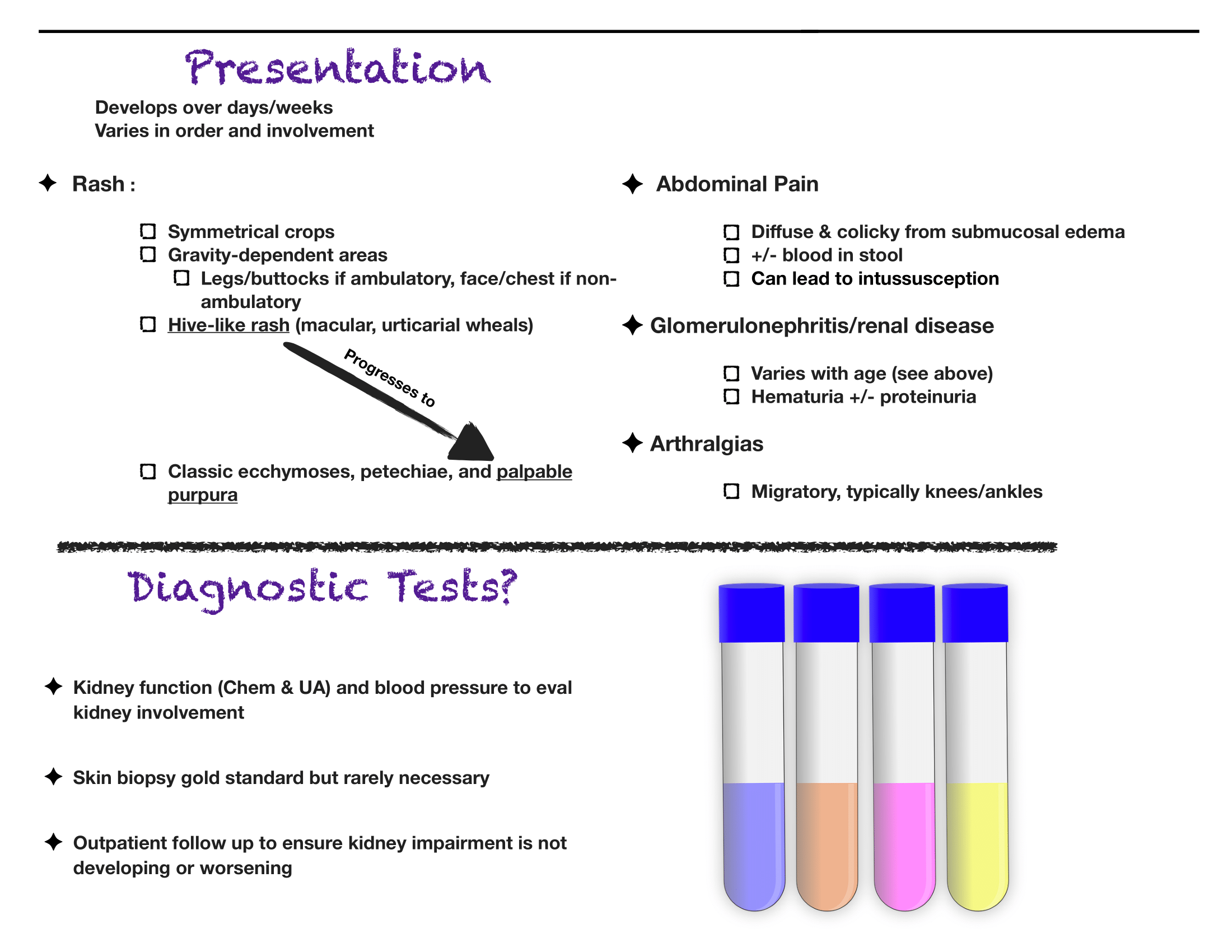

The CACTUS trial was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial prospectively assessing anticoagulation for calf DVTs [1]. Notably, the trial was met with slow enrollment resulting in termination of the study prior to enrollment of the prespecified sample size, meaning that it was underpowered to detect a significant difference between the groups. It only enrolled about half of the participants it had intended to, with an initial 90% power to detect a 70% risk reduction in the composite outcome: development of a proximal DVT or symptomatic PE by day 42. This power study assumed a 10% incidence of the primary outcome in the placebo group.

As you can see, in both groups the progression to proximal DVT or PE was quite low. As there were only 12 total composite events (DVT extension, PE), making a comparison between groups with any degree of certainty impossible. This study met neither their enrollment goals (only enrolling half the participants) nor the predicted incidence of the composite outcome (half the projected amount), so it was quite significantly underpowered to detect a difference.

Notably, the study also did not enroll pregnant women, patients with a previous DVT, recent PE, or recent malignancy. These patients were likely not enrolled due to their higher risk of progression, which may have biased the results towards treatment. As such, the results of this trial could never be applied to these groups.

Unfortunately, given the slow recruitment in the CACTUS trial as well as the low event rate of the composite outcome, the likelihood that this will be studied again in a prospective, double-blinded manner is unlikely. As such, we will need to put the CACTUS trial into context of retrospective evidence to try to identify an ideal practice pattern.

With regard to the retrospective data available:

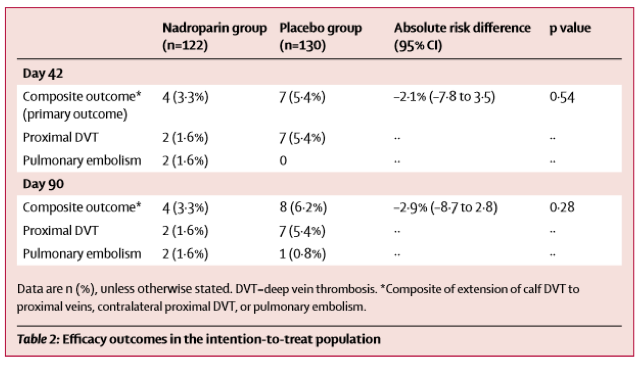

In a 2016 metanalysis, the incidence of PE from DDVT was 0% to 6.2% [median 1.1%] [2], which is in line with the results from the CACTUS trail. As you can see in the chart below, there is some heterogeneity to the results, likely due to the wide variety in study methodology.

Based on the above evidence, what are the best management options? A recent review article (which includes data from CACTUS) offers two suggestions [3]:

The most conservative management will still be anticoagulation of the isolated DDVT. This should be standard for patients with cancer or other pro-thrombotic state that would place the patient at high risk for the development of DVT.

Deferred anticoagulation with follow up ultrasound can be used for patients without significant thrombotic risk factors. You can engage in shared decision making and discuss the risks for bleeding in your patient against the 4-5% risk for clot progression and 1% risk for PE (based on the CACTUS trail as well as retrospective data).

If you decide against anticoagulation in the emergency department, follow up imaging would be recommended in 1-2 weeks to evaluate for progression. This tight follow up window would help to ensure clot progression is identified early and would allow the patient to readdress anticoagulation with his/her primary care physician.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this really great summary! I think you are bringing up a dilemma that we see quite often in the Emergency Department and one that, unfortunately, still doesn’t have much data to help guide our treatment recommendations. The CHEST guidelines for VTE disease were most recently updated in 2016 and do not include the results of the CACTUS trial or the results of the mentioned meta-analysis. Their recommendation is to treat an unprovoked DVT (distal or proximal) with anticoagulation for at least 3 months.

The CACTUS trial questioned if this is required for all patients, primarily focusing on those with an isolated calf DVT. The CACTUS trial had some interesting results, but, like you mentioned, a huge patient population was excluded.. We can only extrapolate this data to a very small group of people: young (average age ~50 years old in the trial), healthy and without any risk factors for VTE. Also, the study drug utilized in the trial was nadroparin, a low molecular weight heparin, which is not available in the US. It would have been more applicable to clinical practice if this trial had utilized a direct-oral anticoagulant like rivaroxaban or apixaban. If these were used the safety results could have potentially been reduced.

So the question remains… to anticoagulate or not to anticoagulate? Here are my final thoughts:

The patients you can think about deferring anticoagulation are those without any VTE risk factors (cancer, obesity, immobility, those on estrogen therapy etc.).

As mentioned, this should be a discussion with the patient so they understand the risk of deferring anticoagulation. They should have adequate follow-up and understand the signs and symptoms of a pulmonary embolism.

The patients that should be anticoagulated are those that have any risk factor for VTE or patients from the previous point that choose treatment.

The anticoagulant should be selected by keeping patient specific factors in mind like past medical history, renal function and current medications

Unlike the CACTUS trial, try and prescribe oral therapy. Your patients will thank you if they don’t have to inject themselves daily.

Kelsea Caruso, PharmD

Emergency Medicine Clinical Pharmacist

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] LaPlant W, Ford W. (2019, May 6). Anticoagulation in distal DVT. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Caruso K]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/distal-dvt

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Resources

Righini M, Galanaud J, Guenneguez H, et al. Anticoagulant therapy for symptomatic calf deep vein thrombosis ( CACTUS ): a randomised , double-blind , placebo-controlled trial. 2017;3(December 2016). doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30131-4.

Wu AR, Garry J, Labropoulos N, Brook S. Incidence of pulmonary embolism in patients with isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2016;5(2):274-279. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2016.09.005.

Robert-ebadi H, Righini M. Management of distal deep vein thrombosis ☆. Thromb Res. 2017;149:48-55. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.11.009.

Bad Blood

Written by: Ade Akhetuamhen, MD (NUEM PGY-2) Edited by: Spenser Lang, MD (NUEM Alum ‘18) Expert commentary by: Matthew Levine, MD

Expert Commentary

Dr Akhetuamhen has provided a nice quick reference for topical hemostatic agents (THAs). These agents have become more relevant in recent years, particularly in prehospital care, as the prehospital emphasis has shifted from resuscitating hemorrhage more towards hemorrhage control. Much of our knowledge of these dressings come from battlefield studies of major hemorrhage. Their use has been formally endorsed by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma in 2014, particularly for junctional site hemorrhaging. Dr Akhetuamhen has listed the properties of the ideal THA. No current product fulfills all of these criteria.

Much of what we know about these agents comes from military studies. There are limitations to these studies. There are fewer human studies, and these tend to be retrospective, observational, and based on questionnaires. The possibility of reporting bias exists in these studies and study design made it impossible to control for the type of wound. There are far more animal studies. Animal studies allow for the ability to control for wound type, but are more difficult to simulate real life wounds from missiles or shrapnel.

Hemcon and Quickclot products were the earliest products studied by the military and became the early THA gold standards after they were determined to be more effective than standard gauze. An earlier concern for Quickclot was exothermic reactions from the activated products that caused burns to patients. As Quickclot transitioned its active ingredient from zeolite to kaolin, this concern diminished. Quickclot is available in a roll called Combat Gauze that is favored by the military and available in our trauma bay.

Finally, there are some important practical tips for using these products. THAs are not a substitute for proper wound packing and direct pressure. Most topical hemostatic agent failures in studies were from user failure! THAs must come into contact with the bleeding vessel to work. Simply applying the THA over the bleeding areas does not mean it is contacting the bleeding vessel. The product may need to be trimmed, packed, shaped or molded in order to achieve this. Otherwise it is simply collecting blood. After it is properly applied, pile gauze on top of it and give firm direct pressure for several minutes before checking for effectiveness.

See what THA(s) you have available in your trauma bay, it is nice to know ahead of time before presented with a hemorrhaging patient what you have and in what form (a roll, sponge, wafer, etc). Find out how the product is removed. It may not be relevant to the patient’s ED stay but at some point the dressing needs to come off. Some are left to fall off on their own. The chitosan products are removed by soaking them. When soaked, the chitosan turns slimy and can be slid off atraumatically.

Matthew Levine, MD

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Medicine

How to Cite this Blog

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Akhetuamhen A, Lang S (2018, October 29). Bad Blood. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/bad-blood

Other Blogs You May Enjoy

Supratherapeutic INR

Written by: Luke Neill, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Logan Weygandt, MD (NUEM Alum '17) Expert commentary by: Abbie Lyden, PharmD BCPS

Expert Commentary

This is an excellent post on the management of supratherapeutic INR in patients taking vitamin K antagonist therapy – and as you described, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Warfarin is notorious for being one of the most difficult medications to manage based on narrow therapeutic index, variable dose response, clinically significant diet- and drug- drug interactions, delayed onset and offset of action and the need for frequent monitoring. Fortunately, warfarin does have an antidote in vitamin K. Yet, the choice of when to administer this antidote (and weaknesses of said antidote), along with other therapies including prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) and fresh frozen plasma, are not straightforward and depend upon a number of factors. In addition to your excellent teaching points, I have outlined some additional considerations below.

Life-threatening bleeding

In the setting of life-threatening bleed, guidelines dictate our therapeutic approach, which involves holding warfarin and administering 4-factor PCC and intravenous vitamin K (10mg slow infusion over 20-60 minutes)1.

Minor bleeding

The management of life-threatening bleeding is clear and requires aggressive therapy. But how do we manage the patient who has a moderately elevated INR but only a minor bleed? In the setting of minor bleeding (such as intermittent epistaxis), the goal is restore the INR to target range, without leading to subtherapeutic anticoagulation, thus introducing the risk of thrombosis. There is general consensus regarding holding a dose of warfarin in these scenarios but the choice to administer vitamin K has been debated. The choice of approach should depend upon the perceived risk of bleeding, extent of bleed, site of bleed, INR level (and trend in INR), comorbidities (including indication for anticoagulation) and risk of thromboembolism. The downsides to administering vitamin K are worth mentioning as they are sometimes superseded by our focus on providing active treatment (unquestionably necessary in the case of life-threatening bleed). Excessive vitamin K dosing may result in warfarin resistance for 1-2 weeks which may require extensive bridging therapy once anticoagulation is restarted. For patients with high thromboembolic risk, poor adherence to medications, higher INR goals or comorbidities, this can become complicated and is certainly not without risk.

Elevated INR without bleeding

The 2012 ACCP guidelines recommend administration of oral vitamin K (2.5-5mg) to patients without an active bleed who have an INR>10 (1). Other experts and the 2008 ACCP guidelines use a more conservative cutoff of 9 (2). For those patients with INRs between 4.5 and 10 without evidence of bleeding, the 2012 ACCP guidelines suggest against the routine use of vitamin K. In this post, you make a great point regarding the management of INRs 5-9 without bleeding. That is, the administration of vitamin K may or may not be administered, depending on the risk of bleeding. Low dose vitamin K administration should be more strongly considered in patients with high risk bleed (elderly, prior bleed) and lower risk of thromboembolism. A retrospective review of 633 patients with elevated INR >6 identified risk factors for slow spontaneous lowering of supratherapeutic INR, including older age, higher index INR, lower warfarin maintenance dose, decompensated heart failure and active cancer (3). Knowledge of these risk factors may help guide decision-making when considering whether or not to administer vitamin K.

Urgent Surgery/Procedure

Patients meriting further discussion are those taking vitamin K antagonists who require urgent (same day) surgeries or invasive procedures. These patients are managed in a similar fashion to those with life threatening bleeding – that is to say, vitamin K (10mg IV) and 4-factor PCC. Of note, for those patients who can wait 24 hours, low dose vitamin K (1-2.5mg PO) is generally adequate for INR reversal. In these cases, 4-factor PCC and intravenous vitamin K can be avoided.

Specific Treatments

With regards to the specific treatments to reverse supratherapeutic INR, some points to keep in mind:

Vitamin K (phytonadione): typically administered intravenous or orally.

For life-threatening bleed, intravenous vitamin K is preferred due to the faster onset of action (which is still delayed, ~3-8 hours) but faster than oral (onset ~24 hours)

Subcutaneous administration is generally avoided if possible due to erratic absorption

Intramuscular administration is generally avoided due to the risk of hematoma in an anticoagulated or overanticoagulated patient

2. Prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC):

4-factor PCCs (factors II, VII, IX, X): preferred first line therapy for life-threatening bleed

Activated PCC (aPCC): factor VII is mostly present in the activated form, which is potentially more prothrombotic than unactivated PCC

Some PCC products contain heparin and should NOT be administered in a patient with a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

In short, patients with life-threatening bleed taking vitamin K antagonist therapy require urgent evaluation and treatment with PCC and IV vitamin K. Treatment with PCC is paramount as INR can be corrected within 30 minutes, as opposed to several hours after IV vitamin K administration (onset dependent upon liver synthesis of new coagulation factors). For those patients with supratherapeutic INR without bleeding and patients with minimal bleed, a more gentle approach is indicated, which involves omission of warfarin dose +/- low doses of oral vitamin K to ensure correction of INR and prevention of bleeding but not subtherapeutic anticoagulation. Lastly, it is important to identify if there are additional explanations for the supratherapeutic INR by verifying if the patient was taking the appropriate dose of warfarin or whether they have recent dietary changes or new medications which may interact. If therapy is to be resumed, these questions are particularly helpful when deciding how and when to restart anticoagulation.

Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e152S.

Ansell J, Hirsch J, Hylek E, et al. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):160S.

Hylek EM, Regan S, Go AS, Hughes RA, Singer DE, Skates SJ. Clinical predictors of prolonged delay in return of the international normalized ratio to within the therapeutic range after excessive anticoagulation with warfarin. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(6):393.

Abbie Lyden, PharmD BCPS

Clinical Pharmacist, Emergency Medicine | Associate Professor, Pharmacy Practice

Residency Program Director, PGY2 EM Pharmacy

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Neill L, Weygandt L (2018, October 8). Supratherapeutic INR. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Lyden A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/supratherapeutic-inr

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Transfusion Reactions In The ED

Blood products, despite what may be commonly believed, are a scarce and valuable resource. While overall, there are many systems to ensure the safety of the products, any transfusion poses a certain degree of risk. We review the spectrum of transfusion reactions, from the common to the uncommon.

Journal Club: Immediate Discharge Home of Newly Diagnosed VTE

Clinical Question: Can low-risk patients with a newly diagnosed VTE in the ED be safely discharged home?

An overview of Massive Transfusion Protocol