Approach to recognition and management of severe asthma exacerbations

Crashing Patient on a Ventilator

Written by: Patrick King, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Adesuwa Akehtuamhen, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary by: Matt McCauley, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary

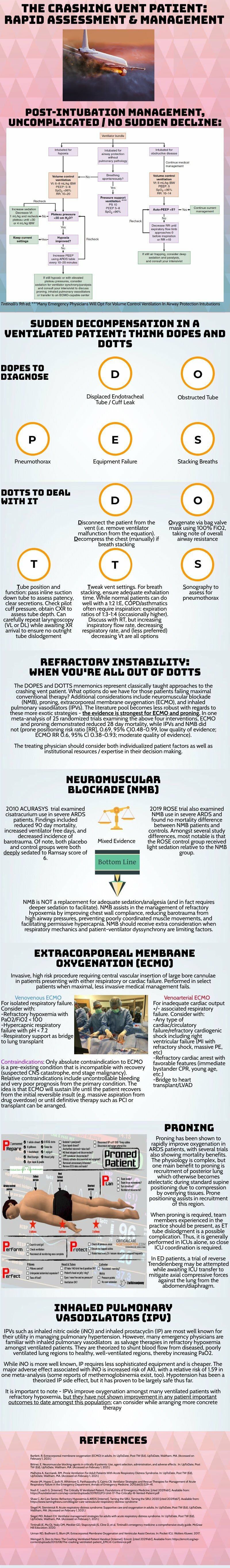

Thank you for this succinct summary of an incredibly important topic. We as emergency physicians spend a lot of time thinking about peri-intubation physiology but the challenges do not end once the plastic is through the cords. The frequency with which our ventilated patients stay with us in the ED has been increasing for years and will likely continue to do so1. This means that managing both acute decompensation and refractory hypoxemia needs to be in our wheelhouse.

The crashing patient on the ventilator can be truly frightening and your post effectively outlines a classic cognitive forcing strategy for managing these emergencies. A truism in resuscitation is to always rule out the easily correctable causes immediately. In this case, it means removing the complexity of the ventilator and making things as idiot-proof as possible. Once you’ve ruled out the life threats like pneumothorax, tube displacement, and vent malfunction, you can try to bring their sats up by bagging. Just make sure that you have an appropriately adjusted PEEP valve attached to your BVM for your ARDS patients; the patient who was just requiring a PEEP of 15 isn’t going to improve with you bagging away with a PEEP of 5.

Once you’ve gotten the sats up and the patient back on the vent, your ventilator display can provide you with further data as to why your patient decompensated. Does the flow waveform fail to reach zero suggesting breath stacking and a need for a prolonged expiratory time? Is the measured respiratory rate much higher than your set rate with multiple breaths in a row indicating double-triggering? The measured tidal volume might fall short of your set tidal volume. This points towards a circuit leak, cuff leak, or broncho-pleural fistula. Maybe you’re seeing the pressure wave dip below zero mid-inspiration and the patient is telling you that they are in need of faster flow, a bigger breath, or deeper sedation. In these situations, your respiratory therapist is going to be your best friend in managing this patient-ventilator interactions2.

As your post alludes to, sometimes patients remain hypoxemic despite our usual efforts and refractory hypoxemia can be an intimidating beast when you’ve got a busy ED burning down around you. If your cursory efforts to maintain vent synchrony by playing with the ventilator dials have failed, there’s no shame in deepening sedation which will work to decrease oxygen consumption and prevent derecruitment. Once sedated, work with your RT to find appropriate PEEP and tidal volumes to meet your goals.

Most patients can be managed with usual lung-protective ventilation but some patients will require more support and you’ve correctly identified several salvage therapies. My general approach is to pursue prone positioning in any patient with a P:F ratio approaching 150 despite optimal vent settings as it has the only strong mortality benefit of the therapies outlined above. Proning in the ED is resource intensive and is probably better pursued as a department-wide protocol rather than you and your charge nurse trying to figure it out in the middle of the night3.

As you’ve pointed out, the neuromuscular blockade has more limited evidence and is not required for prone ventilation. Upstairs, we accomplish this with continuous infusions but in the ED you may be more comfortable using intermittent boluses of intubation dose rocuronium. Just make sure your patient is unarousable. I reach for this if I’m unable to achieve ventilator synchrony with sedation alone as it allows for very low tidal volumes and inverse ratio ventilation. I see inhaled pulmonary vasodilators in a similar light: there’s no data on patient-oriented outcomes but they can make your numbers look prettier while you wait for more definitive interventions such as transfer.

This finally brings me to VV ECMO for refractory hypoxemia. It’s worth considering that while there is some evidence for a mortality benefit for ECMO in ARDS, the evidence base is mixed. The CESAR trial did show a mortality benefit in patients transferred to an ECMO center but only 76% of patients actually received ECMO upon transfer4. The larger and more recent EOLIA trial failed to demonstrate this improvement in mortality5. The conclusion I take from this is that treatment at a high volume center matters and that a boarding patient with refractory hypoxemia warrants an early consideration for transfer to a tertiary center if high-quality ARDS care can’t be accomplished upstairs at your shop.

References

Mohr NM, Wessman BT, Bassin B, et al. Boarding of Critically Ill Patients in the Emergency Department. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(8):1180-1187. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004385

Sottile PD, Albers D, Smith BJ, Moss MM. Ventilator dyssynchrony – Detection, pathophysiology, and clinical relevance: A Narrative review. Ann Thorac Med. 2020;15(4):190. doi:10.4103/atm.ATM_63_20

McGurk K, Riveros T, Johnson N, Dyer S. A primer on proning in the emergency department. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1703-1708. doi:10.1002/emp2.12175

Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2009;374(9698):1351-1363. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2

Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. Published online May 23, 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800385

Matt McCauley, MD

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] King, P. Akehtuamhen, A. (2022, Feb 28). Crashing Ventilator Patient. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by McCauley, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/crashing -vent-patient.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism

Written by: Megan Chenworth, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Abiye Ibiebele, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that focused transthoracic cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) can help identify PE in tachycardic or hypotensive patients? (It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 92% for PE in patients with an HR>100 or SBP<90, and approaches 100% sensitivity in patients with an HR>110 [1]). Have a hemodynamically stable patient with PE and wondering how to risk stratify? FOCUS can identify right heart strain better than biomarkers or CT [2].

Who to FOCUS on?

Patients presenting with chest pain or dyspnea without a clear explanation, or with a clinical concern for PE. The classic scenario is a patient with pleuritic chest pain with VTE risk factors such as recent travel or surgery, systemic hormones, unilateral leg swelling, personal or family history of blood clots, or known hypercoagulable state (cancer, pregnancy, rheumatologic conditions).

Patients presenting with unexplained tachycardia or dyspnea with VTE risk factors

Unstable patients with undifferentiated shock

When PE is suspected but CT is not feasible: such as when the patient is too hemodynamically unstable to be moved to the scanner, too morbidly obese to fit on the scanner, or in resource-limited settings where scanners aren’t available

One may argue AKI would be another example of when CT is not feasible (though there is some debate over the risk of true contrast nephropathy - that is a discussion for another blog post!)

How to scan like a Pro

Key is to have the patient as supine as possible - this may be difficult in truly dyspneic patients

If difficulty obtaining views arise, the left lateral decubitus position helps bring the heart closer to the chest wall

FOCUS on these findings

You only need one to indicate the presence of right heart strain (RHS).

Right ventricular dilation

Septal flattening: Highly specific for PE (93%) in patients with tachycardia (HR>100) or hypotension (SBP<90) [1]

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

McConnell’s sign

Definition: Akinesis of mid free wall and hypercontractility of apical wall (example below)

The most specific component of FOCUS: 99% specific for patients with HR>100bpm or SBP<90 [1]

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

The most sensitive single component of FOCUS: TASPE < 2cm is 88% sensitive for PE in tachycardic and hypotensive patients; 93% sensitive when HR > 110 [1]

Where to FOCUS

Apical 4 Chamber (A4C) view: your best shot at seeing it all

Find the A4C view in the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line

Optimize your image by sliding up or down rib spaces, sliding more lateral towards the anterior axillary line until you see the apex with the classic 4 chambers - if the TV and MV are out of the plane, rotate the probe until you can see both openings in the same image; if the apex is not in the middle of the screen, slide the probe until the apex is in the middle of the screen. If you are having difficulty with this view, position the patient in the left lateral decubitus.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the normal RV: LV ratio in diastole is 0.6:1. If the RV > LV, it is abnormal. (see in the image below)

Septal flattening/bowing is best seen in this view

McConnell’s sign: akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

McConnell’s Sign showing akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

4. Tricuspid regurgitation can be seen with color flow doppler when positioned over the tricuspid valve

Tricuspid regurgitation seen with color doppler flow

5. TAPSE

Only quantitative measurement in FOCUS, making it the least user-dependent measurement of right heart strain [3]

A quantitative measure of how well the RV is squeezing. RV squeeze normally causes the tricuspid annulus to move towards the apex.

Fan to bring the RV as close to the center of the screen as possible

Using M-mode, position the cursor over the lateral tricuspid annulus (as below)

Activate M-mode, obtaining an image as below

Measure from peak to trough of the tracing of the lateral tricuspid annulus

Normal >2cm

How to measure TAPSE using ultrasound

Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view - a good second option if you can’t get A4C

Find the PSLA view in the 4th intercostal space along the sternal border

Optimize your image by sliding up, down, or move laterally through a rib space, by rocking your probe towards or away from the sternum, and by rotating your probe to get all aspects of the anatomy in the plane. The aortic valve and mitral valve should be in plane with each other.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the RV should be roughly the same size as the aorta and LA in this view with a 1:1:1 ratio. If RV>Ao/LA, this indicates RHS.

Septal flattening/bowing of the septum into the LV (though more likely seen in PSSA or A4C views)

Right heart strain demonstrated by right ventricle dilation

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) view: the second half of PSLA

Starting in the PSLA view, rotate your probe clockwise by 90 degrees to get PSSA

Optimize your image by fanning through the heart to find the papillary muscles - both papillary muscles should be in-plane - if they are not, rotate your probe to bring them both into view at the same time

Important findings:

Septal flattening/bowing: in PSSA, it is called the “D-sign”.

“D-sign” seen on parasternal short axis view. The LV looks like a “D” in this view, particularly in diastole.

Subxiphoid view: can add extra info to the FOCUS

Start just below the xiphoid process, pointing the probe up and towards the patient’s left shoulder

Optimize your image by sliding towards the patient’s right, using the liver as an echogenic window; rotate your probe so both MV and TV are in view in the same image

Important findings

Can see plethoric IVC if you fan down to IVC from RA (not part of FOCUS; it is sensitive but not specific to PE)

Plethoric IVC that is sensitive to PE

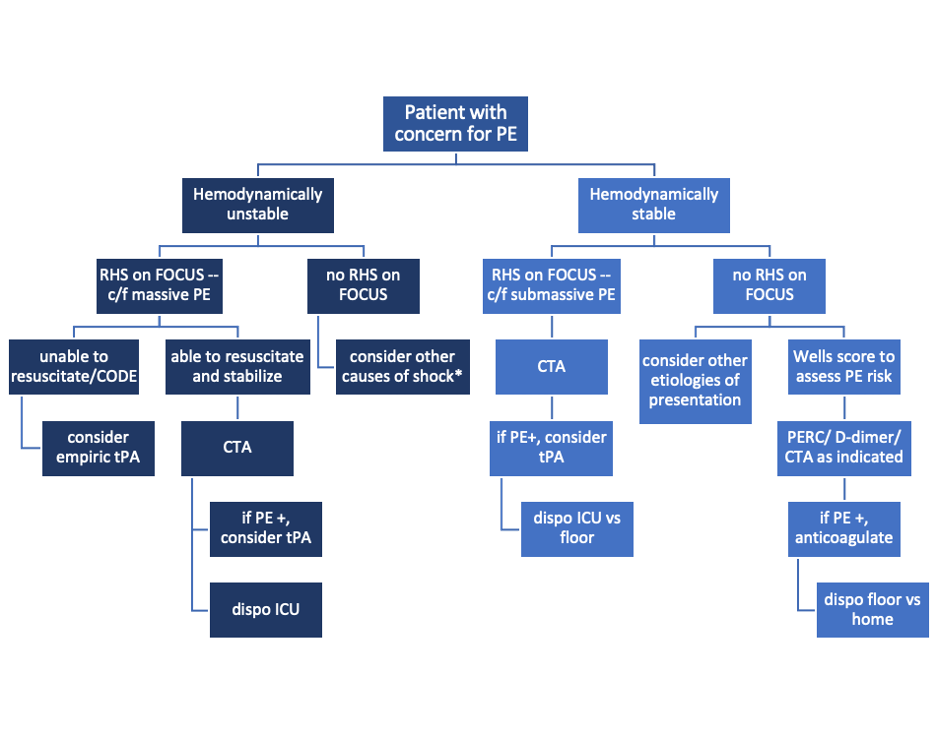

What to do next?

Sample algorithm for using FOCUS to assess patients with possible PE.

*cannot completely rule out PE, but negative FOCUS makes PE less likely

Limitations to keep in mind:

FOCUS is great at finding heart strain, but the lack of right heart strain does not rule out a pulmonary embolism

Systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the overall sensitivity of FOCUS for PE is 53% (95% CI 45-61%) for all-comers [5]

Total FOCUS exam requires adequate PSLA, PSSA, and A4C views – be careful when interpreting inadequate scans

Can see similar findings in chronic RHS (pHTN, RHF)

Global thickening of RV (>5mm) can help distinguish chronic from acute RHS

McConell’’s sign is also highly specific for acute RHS, whereas chronic RV failure typically appears globally akinetic/hypokinetic

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Right Heart Strain at 5-Minute Sono: http://5minsono.com/rhs/

Ultrasound GEL for Sono Evidence: https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/EJHu_SYvE4oBT4igNHGBrg, https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/OOWIk1H2dePzf_behpaf-Q

The Pocus Atlas for real examples: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/echocardiography-2

The Evidence Atlas for Sono Evidence: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/ea-echo

References

Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, Shaw DL, Stone MB, Schick A, Vrablik M, Kennedy Hall M, Hall J, Liteplo AS, Haney RM, Hun N, Liu R, Moore CL. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Nov;26(11):1211-1220. doi: 10.1111/acem.13774. Epub 2019 Sep 27. PMID: 31562679.

Weekes AJ, Thacker G, Troha D, Johnson AK, Chanler-Berat J, Norton HJ, Runyon M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Markers in Normotensive Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Sep;68(3):277-91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.027. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26973178.

Kopecna D, Briongos S, Castillo H, Moreno C, Recio M, Navas P, Lobo JL, Alonso-Gomez A, Obieta-Fresnedo I, Fernández-Golfin C, Zamorano JL, Jiménez D; PROTECT investigators. Interobserver reliability of echocardiography for prognostication of normotensive patients with pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014 Aug 4;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-29. PMID: 25092465; PMCID: PMC4126908.

Hugues T, Gibelin PP. Assessment of right ventricular function using echocardiographic speckle tracking of the tricuspid annular motion: comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Echocardiography. 2012 Mar;29(3):375; author reply 376. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01625_1.x. PMID: 22432648.

Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:714–23.e4.

Expert Commentary

RV function is a frequently overlooked area on POCUS. Excellent post by Megan looking specifically at RV to identify hemodynamically significant PEs. We typically center our image around the LV, so pay particular attention to adjust your views so the RV is optimized. This may mean moving the footprint more laterally and angle more to the patient’s right on the A4C view. RV: LV ratio is often the first thing you will notice. When looking for a D-ring sign, make sure your PSSA is actually in the true short axis, as a diagonal cross-section may give you a false D-ring sign. TAPSE is a great surrogate for RV systolic function as RV contracts longitudinally. Many patients with pulmonary HTN or advanced chronic lung disease can have chronic RV failure, lack of global RV thickening. Lastly remember, that a positive McConnell’s sign is a great way to distinguish acute RHS from chronic RV failure.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Chenworth, M. Ibiebele, A. (2021 Oct 4). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pulmonary-embolism

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pneumothroax

Written by: Morgan McCarthy, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Jon Hung, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that Lung Ultrasound (LUS) has a higher sensitivity than the traditional upright anteroposterior chest X-ray for the detection of a pneumothorax? (LUS has a reported 90.9 for sensitivity and 98.2 for specificity. CXR were 50.2 for sensitivity and 99.4 for specificity). Busy trauma bay? Ultrasound is faster than calling for X-ray. Critically ill patient? Small pneumothoraces are less likely to be missed with ultrasound. To take your Sono Skills to the next level, read on:

Beyond the classic trauma patient during your E-Fast Exam, who else does the Sono-Pros scan?

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax: the classic scenario is a tall, young adult, with symptoms such as breathlessness, along with potentially those with risk factors of pneumothoraxes such as smoking, male sex, family history of pneumothorax

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: those with underlying lung disease including but not limited to COPD, tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, pneumonocystis carini, lung cancer, sarcoma involving the lung, sarcoidosis, endometriosis, cystic fibrosis, acute severe asthma, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Of course, traumatic pneumothorax, especially in penetrating trauma or blunt trauma with broken ribs

Don’t forget iatrogenic causes of pneumothorax including transthoracic needle aspiration, subclavian vessel puncture, thoracentesis, pleural biopsy, and mechanical ventilation

SonoPro Tips - How to scan like a Pro

The key is to have the patient completely supine - air rises! - with the probe in the anterior field in sagittal orientation pointing towards the patient's head.

It is commonly taught to start at the second intercostal space, midclavicular line, and scan down a few lung spaces to at least the 4th intercostal space, however, keep in mind some studies show that trauma supine trauma patients had pneumothoraces seen more commonly in the 5-8 rib spaces.

Important Landmarks

Green = Subcutaneous tissue. Red = Pleural space. Blue = A - lines.

4. Look for lung sliding, improve your image by turning down gain and decrease depth to have lung sliding become clearer

What to Look For:

To Rule-Out a pneumothorax

Lung Sliding - Lung sliding has a negative predictive value of 100% for ruling out a pneumothorax, however only at that interspace

Additional Findings: B-lines and Z lines also help to rule out pneumothorax!

2. To Rule-In a pneumothorax

Lung point - the interface between where lung sliding is happening and where the absence of lung sliding is happening has been shown to have 100% specificity for pneumothorax.

Keep in mind the border of where the heart and lung come in contact and the border where the diaphragm and lung come in contact can cause a false lung point.

The lung point may be hard to find in a larger pneumothorax, and impossible to find in a completely collapsed lung.

3. Next turn on M-mode:

Sandy Beach Shore = Lung sliding (left). Barcode Sign = No lung sliding (right)

What to do next:

Lung sliding = sensitive, Lung point = specific

If you see lung sliding, there is no pneumothorax

If you do not see lung sliding it does not rule in a pneumothorax -> look for a lung point, the interface between where lung sliding is happening and where the absence of lung sliding is happening to rule it in

Always keep in mind other causes that result in lack of lung sliding before management decisions take place!: atelectasis, main-stem intubation, adhesions, contusions, and arrest or apnea. Check out this great table from 5 - Min Sono.

4. If your patient is apneic or has a mainstem intubation look for lung pulse, when the heart beats if the parietal and visceral pleura are touching (no pneumothorax) it will show a pulse at the interfaces of the pleura

5. Sub-Q emphysema - Always look for E - lines. When there is subcutaneous air above the pleural line it creates a false pleural line above the actual pleural. You may also see B-lines obscuring the actual pleural line. This is most likely subcutaneous air and you can not interpret it for a pneumothorax.

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound imaging criteria compendium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(4):487-510.

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Macias, Micheal. TPA, The Pocus Atlas.

Availa, Jacob. 5 minute Sono.

Alrajhi K, Woo MY, Vaillancourt C. Test characteristics of ultrasonography for the detection of pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;141(3):703-708.

Expert Commentary

Morgan went “beyond lung sliding” and dove deep into how to increase your sensitivity & specificity for PTX with POCUS. Supine is ideal to make PTX visible against the anterior chest wall, but if the patient cannot tolerate lying flat, look at the apical pleural superior to the clavicles. First, identify the true pleural line--it should be the bright line just deep to the ribs in your view. SQ emphysema may obscure the view or even mimic the pleura, although its outline is usually more hazy & irregular, a little pressure helps to move the SQ air out of the way can be helpful. Sliding? Great, PTX ruled out. But absent sliding does not automatically mean PTX. Make sure there is no B-line or “lung pulse”, as sometimes pleural adhesion or poor ventilation can cause absent sliding too. Most of the time you don’t need M-mode unless the movement is very subtle and you want to be extra sure. The lung point is pathognomonic for PTX, but don’t waste time digging around for it if the patient is unstable with a good clinical story for PTX > decompress instead!

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] McCarthy, M. Hung J. (2021 Sept 20). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pneumothorax. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pneumothorax

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Basic Capnography Interpretation

Written by: Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Matt McCauley, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: N. Seth Trueger, MD, MPH

Continuous waveform capnography has increasingly become the gold standard of ETT placement confirmation. However, capnography can provide additional valuable information, especially when managing critically ill or mechanically ventilated patients.

Normal Capnography

Phase I (inspiratory baseline) reflects inspired air, which is normally devoid of CO2.

Phase II (expiratory upstroke) is the transition between dead space to alveolar gas.

Phase III is the alveolar plateau. Traditionally, PCO2 of the last alveolar gas sampled at the airway opening is called the EtCO2. (normally 35-45 mmHg)

Phase 0 is the inspiratory downstroke, the beginning of the next inspiration

Figure 1. Normal Capnography Tracing (emDOCs.net)

EtCO2 is only one component of capnography. Measured at the end-peak of each waveform, it reflects alveolar CO2 content and is affected by alveolar ventilation, pulmonary perfusion, and CO2 production.

Figure 2. Factors affecting ETCO2 (EMSWorld)

EtCO2 - PaCO2 Correlation

Correlating EtCO2 and PaCO2 can be problematic, but in general, PaCO2 is almost always HIGHER than EtCO2. Normally the difference should be 2-5mmHg but the PaCO2-EtCO2 gradient is often increased due to increased alveolar dead space (high V/Q ratio), such as low cardiac output, cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolism, high PEEP ventilation.

Important Patterns

Let’s go through a few cases and learn some of the important capnography waveforms to recognize

Case 1: Capnography with Advanced Airway

An elderly gentleman with a history of COPD, CAD & CKD gets rushed into the trauma bay with respiratory distress and altered mental status. You gave him a trial of BiPAP for a few minutes without improvement.

You swiftly tubed the patient. It was not the easiest view, but you advance the ETT hoping for the best. Upon attaching the BVM to bag the patient, you saw this on capnography:

Figure 3. Case 1 (EMSWorld)

Oops, the ETT is in the esophagus, as evidenced by the low-level EtCO2 that quickly tapers off.

2. You remove the ETT, bag the patient up, and try again with a bougie. Afterward, you see…

Figure 4. Capnography with ETT in right main bronchus (EMSWorld)

This suggests a problem with ETT position, most often in the right main bronchus. Notice the irregular plateau--the initial right lung ventilation, followed by CO2 escaping from the left lung. Beware that capnography can sometimes still appear normal despite the right main bronchus placement.

3. You pull back the ETT a few cm and the CXR now confirms the tip is now above the carina. The patient’s capnography now looks like this:

Figure 5. Capnography showing obstruction or bronchospasm (SketchyMedicine)

Almost looks normal but notice the “shark fin” appearance, this is due to delayed exhalation, often seen in airway obstruction and bronchospasms such as COPD or asthma exacerbation.

4. You suction the patient and administer several bronchodilator nebs. The waveform now looks more normal:

Figure 6. Capnography showing normal waveform (SketchyMedicine)

5. However, just as you were about to get back to the workstation to call the ICU, the monitor alarms and you see this:

Figure 7. Sudden loss of capnography waveform (SketchyMedical)

Noticing the ETT still in place with good chest rise, you quickly check for a pulse. There is none.

6. You holler, push the code button and start ACLS with a team of clinicians. With CPR in progress, you notice this capnography:

Figure 8. Capnography during CPR (SketchyMedicine)

Initially, your patient’s EtCO2 was only 7, after coaching the compressor and improving CPR techniques, it increased to 14.

You are also aware that EtCO2 at 20min of CPR has prognostic values. EtCO2 <10 mmHg at 20 minutes suggests little chance of achieving ROSC and can be used as an adjunctive data point in the decision to terminate resuscitation.

7. Fortunate for your patient, during the 3rd round of ACLS, you notice the following:

Figure 9. ROSC on capnography (emDOCs.net)

This sudden jump in EtCO2 suggests ROSC. You stop the CPR and confirm that the patient indeed has a pulse.

8. As you are putting in orders for post-resuscitation care, you notice this:

Figure 10. Asynchronous breathing on capnography (SketchyMedical)

This curare cleft comes from the patient inhaling in between ventilator-delivered breaths and is usually a sign of asynchronous breathing. However, in the post-arrest scenario, it is a positive prognostic sign as your patient is breathing spontaneously. You excitedly call your mom, I meant MICU, about the incredible save.

Case 2: Capnography with Non-intubated Patient

You just hung up the phone with MICU when EMS brings you a young woman with a heroin overdose. She already received some intranasal Narcan from EMS but per EMS report patient is becoming sleepy again.

She mumbles a little as you shout her name, and as you put an end-tidal nasal cannula on her, you saw this:

Figure 11. Hypoventilation on capnography (emDOCs.net)

Noticing the low respiratory rate and high EtCO2 value, you recognize this is hypoventilation.

2. But very soon she becomes even less responsive and the waveform changed again:

Figure 12. Airway obstruction on capnography (emDOCs.net)

The inconsistent, interrupted breaths suggest airway obstruction, while the segments without waveform suggest apnea. You have to act fast.

3. By then your nurse has already secured an IV, so you pushed some Narcan. However, in the heat of the moment, you gave the whole syringe. The patient quickly woke up crying and shaking.

Figure 13. Hyperventilating on capnography (emDOCs.net)

She was quite upset and hyperventilating. The waveform reveals a high respiratory rate and relatively low EtCO2.

As much as you are a little embarrassed by putting the patient into florid withdrawal, you know it could have been a lot worse. Walking away from the shift, you think about how many times capnography has assisted you during those critical moments. “Hey, perhaps we should buy a capnography instead of a baby monitor,” you ask your wife at dinner.

Additional Resources

This website provides a tutorial and quiz on some of the basic capnography waveforms.

References

American Heart Association. 2019 American Heart Association Focused Update on Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support. Circulation. 2019; 140(24). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000732

Brit Long. Interpreting Waveform Capnography: Pearls and Pitfalls. emDOCs.net. www.emdocs.net/interpreting-waveform-capnography-pearls-and-pitfalls/, accessed May 12, 2020

Capnography.com, accessed May 12, 2020

Kodali BS. Capnography outside the operating rooms. Anesthesiology. 2013 Jan;118(1):192-201. PMID: 23221867.

Long, Koyfman & Vivirito. Capnography in the Emergency Department: A Review of Uses, Waveforms, and Limitations. Clinical Reviews in Emergency Medicine. 2017; 53(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.08.026

Nassar & Schmidt, Capnography During Critical Illness. CHEST. 2016; 249(2). https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-1369

Sketchymedicine.com/2016/08/waveform-capnography, accessed May 13, 2020

Wampler, D. A. Capnography as a Clinical Tool. EMS World. www.emsworld.com/article/10287447/capnography-clinical-tool. June 28, 2011. Accessed May 13, 2020

Expert Commentary

This is a nice review of many of the intermediate and qualitative uses of ETCO2 in the ED. For novices, I recommend a few basic places to start:

Confirmation of intubation. Color change is good but it’s just litmus paper and gets easily defeated by vomit. Also, in low output states, it may not pick up. Further, colorimetric capnographs require persistent change over 6 breaths, not just a single change. Waveform capnography uses mass spec or IR spec to detect CO2 molecules. There are so many uses, it’s good to have, I don’t see why some are resistant to use this better plastic adapter connected to the monitor vs the other, worse, plastic adapter.

a. The mistake I have seen here is assuming a lack of waveform is due to low cardiac output, ie there’s no waveform because the patient is being coded, not because of esophageal intubation. There is always *some* CO2 coming out if there is effective CPR; if there isn’t, the tube is in the wrong place. If you really don’t believe it, check with good VL but a flatline = esophagus.

2. Procedural sedation. There’s lots of good work and some debate about absolute or relative CO2 changes or qualitative waveform changes that might predict impending apnea, but for me, the best use is that I can just glance at the monitor for a second or two and see yes, the patient is breathing. No more staring at the chest debating whether I see chest rise, etc. It’s like supervising a junior trainee during laryngoscopy with VL: it’s anxiolysis for me.

a. Using ketamine? Chest movement or other signs of respiratory effort without ETCO2 waveform means laryngospasm. Jaw thrust, bag, succinylcholine (stop when better).

3. Cardiac arrest.

a. Quality of CPR. Higher number means more output. Can mean the compressor needs to fix their technique, or more often, is tiring out and needs a swap.

b. ROSC. There can be a big jump (eg from 15 to 40) when ROSC occurs. Very helpful.

c. Ending a code. 20 mins into a code, if it’s <10 during good CPR, the patient is unlikely to survive. I try to view this as confirming what we know – it’s time to end the code. The mistake here is to not end a code that should otherwise end because the ETCO2 is above 10; it doesn’t work like that, it’s a 1-way test.

4. Leak. One waveform shape I wanted to add that I find helpful: if the downstroke kinda dribbles down like a messy staircase, it’s a leak. Can be an incomplete connection (eg tubing to the vent) or the balloon is too empty or full.

Seth Trueger, MD, MPH

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Luo, S., McCauley M. (2021, Sept 9). Basic Capnography Interpretation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Trueger N.S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/capnography

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Seasonal Influenza

Written by: Logan Wedel, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Laurie Aluce, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: Gabrielle Ahlzadeh, MD (NUEM ‘19)

Expert Commentary

Thank you for the concise and informative resource guide. Don’t we all yearn for the days when patients with myalgias and fever were typically diagnosed with influenza and sent on their merry way? Believe it or not, there are some interns who may go their entire first winter as physicians without diagnosing influenza.

A large part of our jobs as emergency medicine physicians is reassurance. Patients want to know they are okay, but they always want something to make them feel better faster, which is true for influenza as well as coronavirus. And while most young, healthy patients do not need treatment for influenza, another consideration is time lost from work, even though symptom duration is really only decreased by one day. However, for some individuals, those one to two days of work may be essential, in which case, a prescription should be considered if the patient presents within 48 hours of symptom onset. For all other healthy adults, I discuss the side effects of the medication. Evidence from a Cochrane Review published in 2014 suggests that in healthy adults, the risks of side effects including nausea, vomiting, headaches and psychiatric symptoms likely outweighs any benefit, which again, does NOT include decreased hospitalizations rates or complications. I usually frame it as “yes, your flu symptoms may get better about 16 hours sooner, but you may also have nausea, vomiting and headaches.” Most people, in my experience, will then pass on a prescription for Tamiflu.

Screening for chronic medical conditions, pregnancy, high risk household members is essential in knowing which patients require treatment. High level athletes is another patient population where treatment may be considered to allow them to get back to training faster but also to minimize spread to the rest of the team.

Visits for influenza are also a great time to discuss vaccination with patients, especially during the current pandemic. Emphasis should be placed on how vaccines prevent life threatening complications from influenza and diminish symptom severity. This is a perfect time for vaccine education to hopefully prevent future pandemics.

References

Jefferson T et al. Oseltamivir for Influenza in Adults and Children: Systematic Review of Clinical Study Reports and Summary of Regulatory Comments. BMJ 2014. PMID: 24811411.

Gabrielle Ahlzadeh, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

University of Southern California

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Wedel, L. (2021, May 17). Seasonal Influenza. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Ahlzadeh, G]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/seasonal-influenza

Other Posts You May Enjoy

D-Dimer How To

Written by: Pete Serina, MD, MPH (PGY-2) Edited by: Laurie Aluce, MD (PGY-3) Expert Commentary by: Timothy Loftus, MD, MBA

Expert Commentary

Kudos to Drs. Aluce and Serina on a well-written, visually appealing infographic on the use and application of d-dimer testing in the ED. I would like to add a couple points of emphasis and elaboration, albeit in a less visually appealing and therefore more cumbersome format…

1. The most important step in any diagnostic algorithm for PE is the first question -- do you really think this patient could have a PE? It seems that PE is considered on the differential for nearly every patient in the ED. There’s plenty of data out there to suggest that even seasoned clinicians drastically overestimate the probability of PE.

2. Risk stratification - whether using an experienced physician’s clinical gestalt, Wells, or Revised Geneva Score - is the first step prior to the potential (mis)application of PERC. This can be a common pitfall in the diagnostic evaluation of PE, as PERC is only recommended in the low-risk patient population. There is no evidence to convincingly support its use in non-low-risk populations. Take for example a young cancer patient with dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain - a mistake would be to apply PERC to this patient prior to appropriate risk-stratification.

3. PERC is not perfect - however the evidence is pretty robust. Use caution in settings with a relatively high prevalence of PE. Additionally, PERC is a rule-out criteria, not a risk stratification tool.

4. While the authors did not mention specifically the use of high sensitivity d-dimer testing in pregnant patients, this is a topic of much discussion as of late. The first study to prospectively evaluate the utility of d-dimer testing in pregnancy was published in 2018 by Righini and co-authors (of Revised Geneva Score fame). Interestingly, the use of d dimer testing in pregnancy is a practice currently recommended against by the American Thoracic Society 2011 guidelines. In the 2018 study, the authors found a clinically meaningful (11%) proportion of patients in whom d-dimer testing could be safely used to exclude PE. As you might imagine, most of this utility was identified in those patients in the first trimester, as d-dimer levels rise during pregnancy (Kline even recommends trimester based cutoffs of 750/1000/1250 although this has yet to be prospectively studied). Further, PE has been cited as the #1 cause of obstetric mortality, which is no laughing matter in the United States where we have many opportunities for improvement with respect to maternal mortality. Muddying the waters further, the YEARS algorithm was also adapted for use during pregnancy. Ultimately, many of us await the next iteration of guidelines to support or optimize our diagnostic decision making for VTE in pregnancy, although the data seem very promising for using d-dimer testing in low to moderate risk patients.

5. I would echo the authors for those in the back - age-adjusting the d-dimer threshold is guideline recommended. Unfortunately, significant variability remains given local practice pattern variation, malpractice environment differences, and differences in assay use.

6. The recent PEGeD study (2019) has furthered the discussion on raising d-dimer thresholds for those with low clinical pretest probability (PTP). Importantly, the authors excluded pregnant patients and those who received “major surgery” within the past 3 weeks from this study. Essentially, this was a study that looked at the application of a higher d-dimer threshold in low PTP patients, also known as a risk-adjusted d-dimer approach. This has the potential to reduce CT imaging by 33% with 0 cases of VTE diagnosed at 3 month follow up.

7. Speaking of reducing CTPA imaging, Dr’s Kline, Courtney, and co-authors have recently published that 2.3% of ED patients undergo CTPA scanning, d-dimer was used in <50% of those patients, and increased d-dimer usage was associated with higher PE yield rate. This finding certainly supports local quality improvement efforts aimed at optimizing the utilization of CTPA within the ED….

Unfortunately, at the end of the day, up to 50% of PEs are diagnosed in patients with no apparent risk factors. That makes everything crystal clear, right?

Great job again by Dr’s Aluce and Serina on a concise, visually appealing, excellent overview of d-dimer testing in for PE in the ED.

References:

Kline J. et al. D-dimer concentrations in normal pregnancy: new diagnostic thresholds are needed. Clin Chem. 2005 May;51(5):825-9. PMID: 15764641

Leung AN et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology Clinical Practice Guideline: Evaluation of Suspected Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011. Nov 15;184(10):1200-8 PMID: 22086989

Righini, M., et al. Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism During Pregnancy. A Multicenter Prospective Management Outcome Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Dec 4;169(11):766-773 PMID: 30357273

van der Pol, L. M., et al. Pregnancy-Adapted YEARS Algorithm for Diagnosis of Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 21;380(12):1139-1149 PMID: 30893534

White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-8.

Timothy Loftus, MD, MBA

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University

How to Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Serina P, Aluce, L. (2020, April 27). D-Dimer How To. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Stelter, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/dimer

Other Posts You Might Enjoy

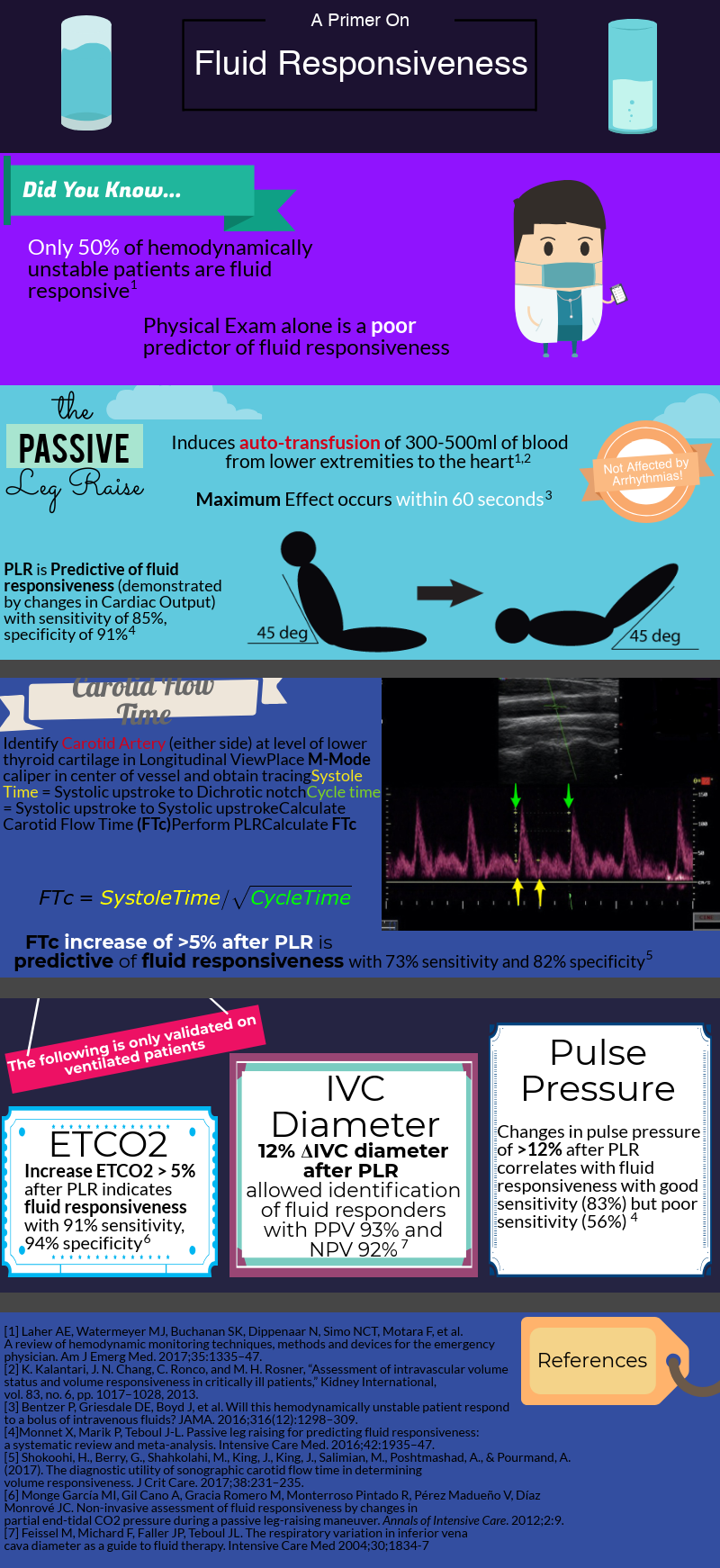

Fluid Responsiveness

Written by: Brett Cohen, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Duncan Wilson, MD (NUEM Alum ‘18) Expert commentary by: Luisa Morales-Nebreda, MD

Expert Commentary

I’ll start by saying that the assessment of a patient’s intravascular volume status and fluid responsiveness is one of the most difficult tasks in clinical medicine, yet it remains a crucial one to adequately manage acute circulatory failure.

After decades of dedicated research to the critically ill, we’ve learned that rigid protocols lead to large amounts of fluid administration, and that fluid overload is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in septic shock and ARDS patients. As you mentioned, only half of hemodynamically unstable patients are fluid responsive, prompting clinicians to describe novel tools/methods to better evaluate fluid responsiveness.

How do we define fluid responsiveness? What are the determinants of fluid responsiveness?

Fluid responsiveness has been defined as a 10-15% increase in cardiac output after a 500 cc bolus fluid challenge. I find this arbitrary definition unhelpful, but I do think that understanding what determines a fluid bolus leading to a preload-responsive state is important.

Figure 1: Frank Starling curve

When giving a fluid bolus, the expectation is that it will increase cardiac preload (by increasing both the stressed volume and mean circulatory filling pressure). Once this condition has been met, the next assumption is that the increase in venous return will lead to a change in stroke volume/cardiac output (venous return = cardiac output). This is the ideal situation! Both ventricles working on the ascending limb of the Frank-Starling curve without any major changes in other determinants of cardiac output (contractility, afterload, diastolic function) Figure 1. Unfortunately, our critically ill patients are not that simple and most times display significant changes in cardiac contractility (e.g., due to acidosis) and afterload (e.g., due to vasoactive agents) that could place them on the flat portion of this curve.

Cardiac Output = Heart Rate x Stroke Volume

Stroke Volume is determined by: contractility, preload, afterload

How do we measure fluid responsiveness?

Despite a great amount of evidence showing that “static” measurements, such as central venous pressure (CVP) are poor predictors of fluid responsiveness, they continue to be widely used. I don’t mean to say that measuring CVPs is useless. After all, perfusion is determined by the pressure gradient between MAP (mean arterial pressure) and CVP, and CVP is a good marker of preload (just NOT of preload responsiveness).

To circumvent this limitation, we can use “dynamic” measurements of heart-lung interactions during mechanical ventilation. Specifically, if changes in intrathoracic pressure under positive pressure ventilation lead to cyclic changes in stroke volume (stroke volume variation or SVV), pulse pressure (pulse pressure variation PVV), or vena cava diameter it indicates that both ventricles are preload-dependent and the patient is fluid responsive. Limitations to these 3 methods include: a) patients need to be mechanically ventilated and without spontaneous breaths (during which changes in intrathoracic pressure become unreliable) b) tidal volume of at least 8 cc/Kg and normal respiratory system compliance (in order to generate significant swings in intrathoracic pressure, tidal volume needs to be on the high end and your lungs/chest wall can’t be stiff).

So you can think about how limited these maneuvers are in the ICU setting. Most intubated patients take spontaneous breaths (unless paralyzed or deeply sedated). If paralyzed for ARDS, they need to be on low-tidal volume ventilation and their lungs are generally pretty stiff.

As you mentioned a maneuver that is unaffected by these limitations is the passive leg raise test (PLR). Importantly, PLR raises preload by shifting venous blood not only from your lower extremities, but mainly from your splanchnic compartment (where ~70% of unstressed volume reservoir lies). This is why in order to adequately perform the maneuver, patients are placed in a semi-recumbent position (rather than horizontal) and the bed is adjusted to 45֯, followed by assessment of cardiac output changes within 60 seconds (NOT blood pressure changes).

PLR is one of the most validated maneuvers for assessment of fluid responsiveness, and as you described, many downstream methods to measure cardiac output have been used, including: a) velocity time integral of the left ventricular outflow tract b) peak velocity of the carotid artery c) changes in end-tidal CO2.

Given the widespread use of critical care echocardiography and their inherent practicality, I think echocardiographic indices are the most useful dynamic parameters to predict fluid responsiveness.

What to expect and my two cents on fluid responsiveness

Given the pace of technology, innovation in hemodynamic monitoring methods will likely improve in the not too distant future. Pocket echo probes and non-invasive wearable sensors measuring cardiac output will make assessment of fluid responsiveness much easier and reliable. Check out:

Michard et al. Intensive Care Medicine (2017) 43:440-442 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00134-016-4674-z

Vincent et al. Intensive Care Medicine (2018) 44:922-924 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00134-018-5205-x

For now, I go to the bedside and after a physical exam perform a basic point-of-care ultrasound to assess heart function, look for interstitial lung edema (B lines) and IVC collapsibility before and after a PLR maneuver (if tolerated). Combining information from these maneuvers not only allows you to better assess a patient’s current volume status and likelihood to be fluid responsive (hyperdynamic LV, absent B lines, collapsible IVC), but can also help you identify what type of shock your patient has and if giving fluid could make things worse (RV failure).

When a patient is likely fluid responsive, I give a small/moderate fluid bolus (250-500 cc) then come back to the bedside to repeat my assessment with the tools I feel most comfortable. Then I ask myself: are things getting better? (Improved mental status/blood pressure, increased in urine output and decreased vasoactive agent requirement). And then do it all over again!

Luisa Morales-Nebreda, MD

Fellow, Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine

Department of Medicine

Northwestern University

How to Cite this Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Cohen B, Wilson D. (2019, Aug 5). Fluid Responsiveness. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Morales-Nebreda L]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/fluid-responsiveness.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

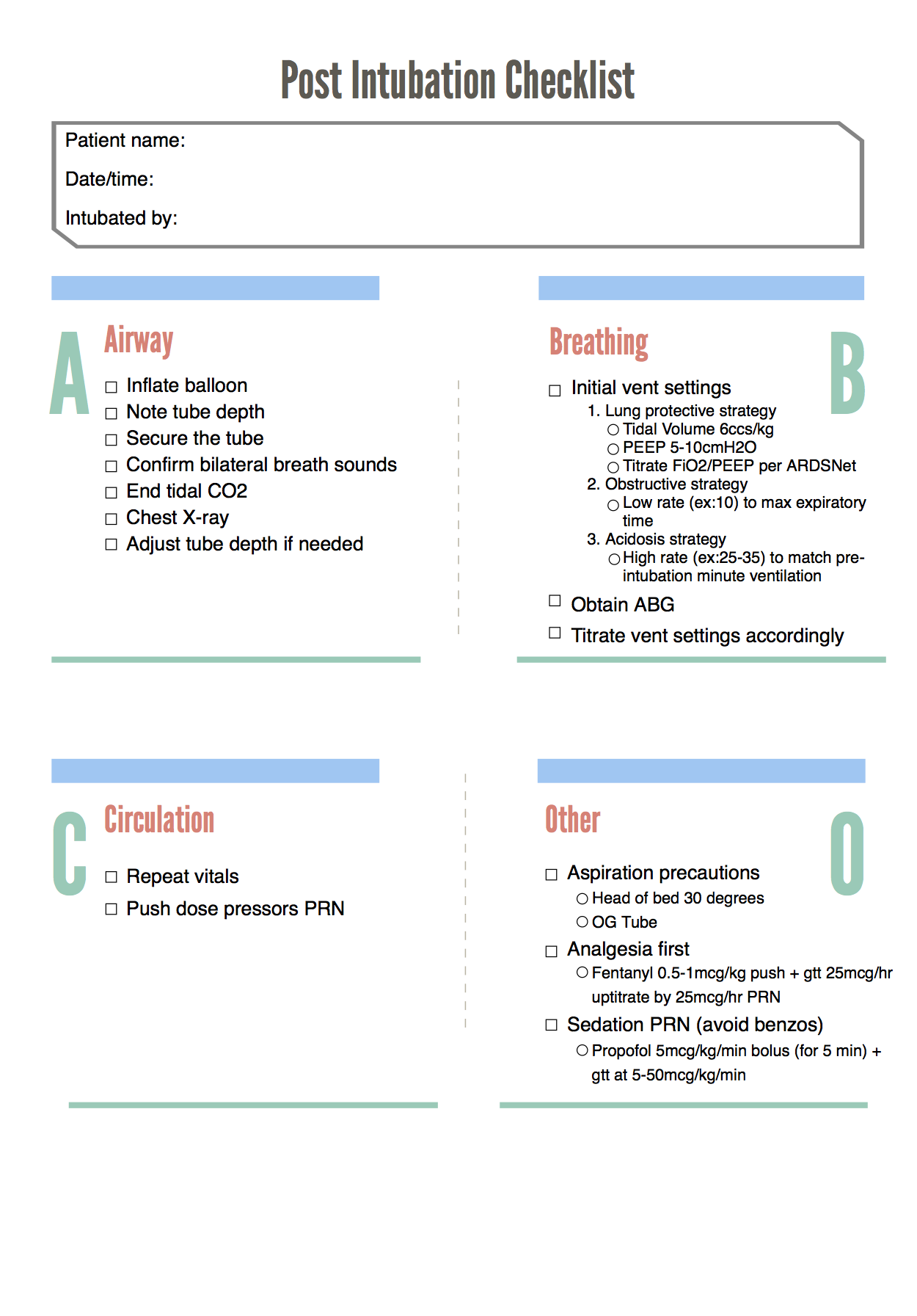

Post-Intubation Checklist

Written by: Andra Farcas, MD (NUEM PGY-2) Edited by: Paul Trinquero, MD (NUEM PGY-4) Expert commentary by: Andrew Pirotte, MD

Developing a Post-Intubation Checklist

Multiple studies have shown checklists in medicine can be beneficial. They have been used to reduce rates of catheter-related blood stream infections and ventilator associated pneumonias and to improve team performance in various settings.

In the ED setting, a peri-intubation checklist for trauma patients resulted in more use of rapid sequence intubation and a trend towards improvement in post-intubation sedation rates.[1] This checklist included meds for pre-intubation (pre-treatment, induction, paralytics) and information about which intubation device was used but had only one line for post-intubation medications and did not include other post-intubation safety measures.

One of the few studies that we could find specifically focused on a post-intubation checklist was a MICU study by McConnell, et al. They looked at the proportion of patients who had an ABG drawn within 60 minutes of mechanical ventilation initiation, as well as rates of respiratory acidosis and acidemia. They found that after initiating a post-intubation checklist and timeout, the rates of ABGs increased, which led to earlier recognition of inappropriate ventilation settings.

There are a lot of pre-intubation checklists available for public use. For example, a great podcast/blogpost by Scott Weingart on the topic was developed into a checklist by Jeffrey Siegler and Christ Huntley. Their versions can be found at https://emcrit.org/emcrit/post-intubation-package/.

Our goal was to design a checklist specifically for the post-intubation setting that could potentially be implemented in our emergency department. We took ideas from aforementioned studies and existing checklists, as well as personal experience. In addition to covering a broad array of post-intubation tasks, we wanted to focus especially on post-intubation sedation and initial vent settings. In regards to these important tasks, what we do in the ED matters. Not only are the first few hours a critical period in the course of illness, but there is significant downstream momentum associated with choices made in the Emergency Department.

The SPICE trial showed a link between deep early sedation and prolonged ventilation and increased mortality.[6] Conversely, an analgesia only, no-sedation approach has been shown to reduce time on the ventilator.[7] Consequently, we advocate for an analgesia-first approach. Fentanyl is a commonly used opioid for this purpose because of its rapid onset and short half-life. An easy starting point is a 0.5 - 1mcg/kg fentanyl push, followed by a drip starting at 25mcg/hr and uptitrated by 25mcg every 15-30 minutes (concurrent with another bolus as needed to control pain).

If pain is under control and additional sedation is needed, there are many options. Propofol is commonly used and is easily titratable. Start with a bolus of 5 mcg/kg/min (for 5 min) and start the drip at 5 to 10 mcg/kg/min, increasing by 5-10mcg/kg/min intervals every 5 min as needed (usual range 5-50mcg/kg/min). In the case of hypotension precluding the use of propofol, consider ketamine. Try to avoid benzodiazepines as these have been shown to increase risk of delirium.

Similarly, the initial vent settings that we chose in the ED matter and they can affect duration of ventilation, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and other patient-oriented outcomes.[2] Not all illnesses requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation are the same and consequently vent-settings are not a one size fits all selection. Try to tailor settings to the individual patient and illness and choose one of the following broad strategies[9]:

Lung Protective Strategy (ARDS, lung injury, default for most patients): goal is to minimize additional injury via volutrauma or barotrauma. Set the tidal volume at 6-8cc per kg (of ideal body weight). Soon after intubation, drop Fio2 to 30% and PEEP to 5cm then titrate according to ARDSNet strategy for goal oxygen saturation 88-95%.

Obstructive Strategy (asthma or COPD): goal is to minimize air trapping by maximizing expiration time. Hence, set a low rate (perhaps 10) which will minimize I:E ratio (perhaps 1:4). Tidal volume can be standard 8cc/kg. This strategy may require permissive hypercapnea.

Severe acidosis (DKA, severe sepsis, etc.): Goal is to mimic the pre-intubation minute ventilation. Set the respiratory rate to match pre-intubation rate (usually at least 25-30).

Below is our designed post-intubation checklist:

Expert Commentary

This column highlights the need for optimized post-intubation management. This process requires attention to detail and patient needs. Effective management not only involves delivery of adequate analgesia and sedation, but also efficient titration of the ventilator. Each of these aspects of post-intubation management can be multi-faceted and challenging. To assist with these processes and to simplify tasks, a checklist can be of great value.

Checklists can help create a stepwise clinical approach and trigger timely delivery of individual tasks. Checklists can also help prevent omission of vital steps. A task as simple as a chest X-ray to confirm endotracheal tube placement and positioning can be overlooked in an emergent situation. The checklist provided in the review provides a simple, direct pathway to assist with post-intubation management, and avoid task omission. In addition, this checklist can help emphasize strategies in the post-intubation period. For example, the use of an “analgesic first” pathway for patient comfort following intubation.

As stated in the blog post, evidence now suggests “analgesic first” pathways improve patient outcomes. The clinician should strive to enhance analgesia prior to escalating sedation. Sedation has its role in post-intubation management, but should be employed only if escalated analgesic efforts fail. “Analgesic first” pathways decrease ICU length of stay, decrease complications, and improve outcomes. In addition to managing patient comfort, the clinician must also focus on optimizing ventilation and oxygenation.

Successful ventilator management requires attention to detail and the clinical scenario. Every patient has different ventilation and oxygenation needs. In addition to frequently reevaluating the patient clinically, a common and effective strategy for optimizing a ventilated patient is use of frequent blood gas measurement. Titration of ventilation and oxygenation can be aided greatly with serial blood gas monitoring. The use of blood gas data can also guide the provider utilizing a specific ventilation strategy (eg Lung-protective strategy). Common problems in early post-intubation management include excessive oxygen delivery and hypoventilation. Both of these can be identified by blood gas sampling. Once optimal ventilation and oxygenation is achieved, the clinician can proceed with further diagnostic and stabilization pathways.

Within the airway community, much focus is placed on optimized laryngoscopy and endotracheal tube delivery, no desaturation during intubation, interesting new equipment, etc. However, managing an airway does not conclude with delivery of the endotracheal tube. All clinicians managing airways would benefit greatly from accompanying this enthusiasm for intubation with focused and detailed care (often supplemented by checklists) in the post-intubation period.

Special thanks to Dr. Jordan Kaylor and Dr. Matthew Pirotte

Andrew Pirotte, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Kansas Hospital

Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Kansas Medical Center

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Farcas A, Trinquero P (2019, February 11). Post-Intubation Checklist [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Pirotte A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/post-intubation

Other Posts You Might Enjoy

References

Conroy, M.J., Weingart, G.S., Carlson, J.N. Impact of checklists on peri-intubation care in ED trauma patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2014; 32:541-544.

Fuller, B.M., Ferguson, I.T., Mohr, N.M., Drewery, A.M., Palmer, C., Wessman, B.T. et al. Lung-Protective Ventilation Initiated in the Emergency Department (LOV-ED): A Quasi-Experimental, Before-After Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2017; 70(3):406-418.

Guthrie, K., Rippey, J. Emergency Department Post-Intubation Checklist. Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2013. https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/273792/emergency-department-post-intubation-checklist-charles-gairdner.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2018.

McConnell, R.A., Kerlin, M.P., Schweickert, W.D., Ahmad, F., Patel, M.S., Fuchs, B.D. Using a Post-Intubation Checklist and Time Out to Expedite Mechanical Ventilation Monitoring: Observational study of a Quality Improvement Intervention. Respiratory Care, 2016; 61(7):902-912.

Nickson, C. Post-intubation care. Life In The Fast Lane, Jan 5 2013. https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/post-intubation-care/. Accessed May 26, 2018.

Shehabi, Y., Bellomo, R., Reade, M., Bailey, M., Bass, F., Howe, B. et al. Early Intensive Care Sedation Predicts Long-Term Mortality in Ventilated Critically Ill Patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2012; 186(8):724-731.

Strøm, T., Martinussen, T., Toft, P. A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomised trial. The Lancet, 2010; 375:475-480

Weingart, S. Podcast 84 – The Post-Intubation Package. EMCrit RACC, Oct 16 2012. https://emcrit.org/emcrit/post-intubation-package/. Accessed May 26, 2018.

Weingart, S. Managing Initial Mechanical Ventilation in the Emergency Department. Annals Of Emergency Medicine, 2016; 68(5):614-61

PJP Pneumonia

Written by: Julian Richardson, MD, MBA (NUEM PGY-2) Edited by: Sarah Sanders, MD (PGY-4) Expert commentary by: Michael Angarone, DO

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is one of the most common AIDS-defining opportunistic infections. It is a fungal disease that affects patients with an impaired immunity. Though it is most commonly associated with HIV and AIDS, the advent of HAART has been associated with a decreasing prevalence of PCP within the HIV population.[6] While the prevalence has been decreasing in the HIV population, it has been increasing in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy.[2]

PCP in the non-HIV patient is becoming an important diagnosis but is less recognized in its early stages. PCP is now mostly diagnosed in the non-HIV population and is associated with higher mortality rates. When comparing PCP in the non-HIV versus HIV population at a single center, over nine years the ratio of non-HIV to HIV PCP patients increased from 1.7 to 5.6 and mortality at day fourteen was 25.9% v 1.4%, respectively.[1] Part of the explanation for the high mortality is that the non-HIV population frequently presents with less symptoms and diagnosis via microscopic examination, which is quicker, more often produces a false-negative compared to real-time polymerase-chain reaction (PCR). By lack of early recognition of PCP in the non-HIV patient and delay in diagnosis, there is a lag in treatment initiation which contributes to the higher mortality rate of the non-HIV patients with PCP.[4]

The clinical features and diagnostic work-up are non-specific and it takes a high-index of clinical suspicion to ensure these patients are treated appropriately. The symptoms of PCP are generally fever, non-productive cough, and progressive dyspnea. With regards to imaging, chest x-ray can be normal in ten percent of these patients or non-specific or inconclusive in thirty percent of these cases. The classic finding on chest x-ray is bilateral reticular infiltrates. Definitive diagnosis is identification of the Pneumocystis organism, which can be done by induced sputum, BAL or lung biopsy. Tests that can identify the organism include PJ DFA or PJ PCR. Induced sputum is just as good as BAL for those with AIDS, which may not be true for other populations. Both the induced sputum culture and BAL are time-consuming and thus PCR is becoming essential to assist with rapid diagnosis.[3,5]

Treatment

Bactrim is the mainstay of treatment for both non-HIV and HIV PCP. In the non-HIV population, Bactrim has been shown to be highly effective and reduces PCP-related mortality by 83%.[7] The prophylactic dose is 80-160mg daily while the treatment dose is 15-20mg/kg/day (both dosed based on the trimethoprim component) divided every six to eight hours for twenty-one days. Adverse reactions are commonly seen in HIV patients and can range from rash, fever, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, azotemia, hepatitis, and hyperkalemia. Given the efficacy of bactrim compared to alternative regimens, it is suggested that supportive care be initiated prior to initiating alternative regimens which are listed below.[5]

Alternative regimens (for treatment) all twenty-one days [5]

Pentamidine (4mg/kg IV daily)

Primaquine (30mg PO daily) + Clindamycin (900mg IV every six hours or 600mg PO every eight hours)

Atovaquone: 750mg PO twice a day

When should steroids be utilized?

Steroids should be given for moderate to severe disease. Moderate to severe disease is defined as PO2 <70mmHg or A-a gradient >35mmHg on room air. The steroids are dosed on a twenty-one day prednisone taper, starting at 40mg PO twice a day. PO regimens taper from 40 mg BID for 5 days to 40 mg daily for 5 days to 20 mg daily for 11 days. If the patient is unable to tolerate PO, IV methyprednisolone can be given at seventy-five percent of the prednisone dose. When considering steroids, early initiation is important and an ABG should be obtained in the emergency department.[5]

Managing Treatment Failure

Clinical failure is defined as lack of improvement or worsening respiratory function after four to eight days of PCP treatment. In patients with mild to moderate disease, this occurs in about ten percent of cases. It should be noted that in the absence of corticosteroids administration, clinical deterioration is not uncommon. ED providers must also consider co-infection with additional microbes, while the inpatient team may discuss bronchoscopy. Depending on disease severity, options for alternative therapies include atovaquone, clinidamycin, and primaquine, however these decisions should be held in conjunction with the patient’s primary physician and/or infectious disease doctor.[5]

Expert Commentary:

Pneumocystis jerovecii pneumonia (PJP) is a life threatening and severe infection that traditionally affected individuals with AIDS. As described in the blog piece the epidemiology of affected patient populations has changed over the past 20 years with effective HIV therapy. It is currently more common to see PJP in persons that have had an organ transplant, stem cell transplant, those on glucocorticoid therapy and those receiving therapies that deplete their T-lymphocytes. A major risk factor for the development of PJP is the use of glucocorticoid medications. On average the median dose of steroids associated with the development of PJP is 30mg/day.[1] At Northwestern Medicine we recently published on our experience with PJP in the Solid Organ Transplant recipient population. We found 15 cases of PJP over a 15 year period. Among these 15 patients, six required intensive care unit management and three (20%) died from there infection. Low absolute lymphocyte count, especially <500 cells/mm3, had the strongest association with development of PJP.[2] This data demonstrates that the key immune cells that help defend against the development of PJP are the lymphocyte and in particular the CD4+ T-lymphocyte. The presentation of PJP in non-HIV infected individuals is similar to that in HIV-infected with fever, dry cough and progressive dyspnea, but many non-HIV infected individuals may present with fulminant respiratory failure. Fortunately trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remains the treatment of choice for this infection, with adjunctive steroids used for those with severe respiratory compromise. For the emergency room provider PJP should be on the list of potential causes of pneumonia or respiratory compromise not just in HIV-infected persons, but in those with compromised immune systems. Like all infections early recognition and early treatment result in better patient outcomes.

Yale SH, Limper AH. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: associated illness and prior corticosteroid therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(1):5.

Werbel WA, Ison MG, Angarone MP, Yang A, Stosor V. Lymphopenia is associated with late onset Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in solid organ transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018 Mar 7:e12876

Michael Angarone, DO

Assistant Professor of Medicine, Infectious Diseases

Northwestern Medicine

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Richardson J, Sanders S (2019, January 14). PJP Pneumonia [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Angarone M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/PJP

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Resources

Bienvenu, Anne-Lise, et al. “Pneumocystis Pneumonia Suspected Cases in 604 Non-HIV and HIV Patients.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 46, 2016, pp. 11–17., doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.018.

“DPDx - Pneumocystis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 Dec. 2017, www.cdc.gov/dpdx/pneumocystis/index.html.

“Fungal Diseases.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 26 Apr. 2017, www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/pneumocystis-pneumonia/index.html.

Liu, Yao, et al. “Risk Factors for Mortality from Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia (PCP) in Non-HIV Patients: a Meta-Analysis.” Oncotarget, Vol. 8, No. 35, Apr. 2017, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927.

“PCP Adult and Adolescent Opportunistic Infection.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 25 July 2017, aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/4/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/321/pcp.

Rosen, Peter, et al. “HIV Infection and AIDS.” Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, Elsevier, 2018.

Stern, Anat, et al. “Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP) in Non-HIV Immunocompromised Patients.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Jan. 2014, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005590.pub3.

VBG vs ABG in the ED

Written by: Emmanuel Ogele, MD (Cook County Stroger PGY-1) Edited by: Spenser Lang, MD (NUEM Alum '18) Expert commentary by: James Walter, MD

ABG’s vs VBG’s in the Emergency Department

Arterial blood gases (ABG’s) – blood sample taken directly from an artery used to gauge the metabolic environment, oxygenation, and ventilation status. Values such as pH, PCO2, PaO2, HCO3, and Base Excess obtained via ABG are considered the gold standard.

Venous Blood gases (VBG’s) – blood sample taken from either peripheral or central veins –can serve as an alternative to an ABG when evaluating patients with metabolic and respiratory disturbances.

Historically, values obtained via VBG have been criticized for a perceived lack of accuracy in all domains.

However, VBGs carry less risk of vascular injury, nerve damage, and cause much less pain to the patient along with lower risk for accidental needle-sticks as compared to ABGs

So the question remains – are values (such as pH, PCO2, and HCO3) truly disparate enough between ABG’s and VBG’s to actually change clinical practice?

Increasing data shows that for most clinical indications, data from VBG correlates well, and are just as useful as that from ABG.[1-4]

Zeserson et. al. conducted a prospective cohort study of 156 critically ill patients in the ED and ICU setting to evaluate the correlation between pH and pCO2 when derived from ABG vs VBG with added pulse oximetry for estimating PaO2 and concluded that arterial and venous pH and PCO2 had good correlation.

Byrne et al conducted a meta – analysis of 1768 subjects from 18 individual studies and found that peripheral VBG correlates well with ABG with respect to pH but found an unacceptably wide 95% prediction interval when looking at the pCO2.

A review article by Kelly AM summarized data comparing ABG and peripheral VBG variables in ED all-comers also concluded that venous pH had sufficient agreement however concluded with a word of caution: there is no data to support that this correlation is maintained in shock states.

Several studies have looked at the correlation between values obtained with VBG and compared them to ABG. These are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlation of VBG to ABG values

** Widest limit of agreement from any single study included in the meta-analysis

For most parameters, there is good correlation. However, there are a few important scenarios that may be exceptions. Not surprisingly, the major exception is PO2; venous PO2 readings do not correlate well with arterial PO2. A workaround to this limitation is to estimate arterial oxygenation using SpO2.

The VBG analysis plus SpO2 provided accurate information on acid–base, ventilation, and oxygenation status for patients in undifferentiated patients ED and ICU.[2]

VBGs are acceptable to use in working up common conditions like COPD and DKA.[5,6] New data could potentially broaden the list of indications for VBG instead of ABG

Ma OJ et al. conducted a prospective trial looking at the utility of ABG in patients presenting to the ED with suspected DKA and found that ABG analysis changed management of DKA 1% of the time and concluded that VBGs are a viable substitute.

Conditions that may affect the reliability of VBG

Hypercapnia.

When comparing VBG and ABGs, the average difference in CO2 reading was 5.7 mmHg. [1]

However, the limits of agreement (-17.4 to +23.9) in this study are too wide to allow reliable quantification of PCO2.

In sum, if you need a precise PCO2 number for clinical decision making, a traditional ABG is preferable.

One such scenario where a true PCO2 can be useful is evaluating for acute hypercapneic respiratory failure; however, a VBG still has some utility.

In the prospective study by AM Kelly 7 a PCO2 value above 45mmHg had a 100% sensitivity for true hypercapnia. This makes a VBG PCO2 value useful in screening for hypercapnia. 5

Shock Pearls

VBGs show increased discordance from ABGs in hypotensive patients.[8]

pH and PCO2 values may be wildly disparate in patients with severe circulatory failure.[9]

In sum, venous blood gases may be increasingly inconsistent with arterial blood gases in patients with increasing degrees of shock. No definitive data exists yet to tell us if VBGs are sufficient to replace ABGs in shock states.

Mixed Acid Base Disorders

There is insufficient evidence to confirm reliability of VBGs in these cases

In summary, VBGs can be used as a reliable alternative to ABGs in many clinical cases. The patients’ benefits of a VBG vs ABG are obvious – decreased pain, complications, and time. Clinical judgment must be used in deciding when to the substitute a VBG for a more traditional ABG. The evidence is mixed, and even non-existent in some clinical scenarios. In the future, noninvasive methods of evaluation, such as transcutaneous PCO2 monitoring and ETCO2, could allow for accurate for non-invasive and monitoring of the metabolic milieu.

Expert Commentary

ABGs vs VBGs in the Emergency Department: Expert Commentary

Thank you for the opportunity to share some thoughts on this topic. The ABG vs VBG debate has been the source of a lot of discussion and at times disagreement between EM and IM. I am hopeful that we are starting to reach consensus on their respective advantages, disadvantages, and indications. When deciding on which test to obtain, here are a few questions to ask yourself:

1. What is my clinical question?

Diagnostic tests should be performed to answer a specific clinical question. Defining this question will help ensure you order the correct test, or perhaps appropriately order no test at all. For blood gas sampling this question might be: “Does my patient with a COPD exacerbation have significant hypercapnia?”; “Is my patient appropriately compensating for his metabolic acidosis?”; “Is my hyperglycemic patient acidotic?” If you can’t articulate a specific question, or if the answer to that question is unlikely to change your management (i.e., a question of “is my patient acidotic?” for a 70-year-old with urosepsis whose blood pressure has responded to 1L of fluid and looks well), then you can probably save your patient an unnecessary blood draw and avoid blood gas sampling altogether. This is certainly an issue for us in the ICU. Patients with arterial lines will have standing Q6hr ABG orders for 2 days before anyone asks if those blood draws are actually changing our management. Don’t order an ABG or VBG just because a patient has sepsis, or they have COPD, or you are “screening for badness.” Using a POC or rapid VBG with a metabolic profile to rapidly obtain lab values for patients presenting to the ER is reasonable. Outside of this situation, try to make sure you are asking a specific question and that answering that question is likely to change what you do.

2. Am I screening for hypercapnia?

If your clinical question is, “is my patient hypercapnic?” then a VBG is a great test. As noted above, a PvCO2 < 40 mmHg excludes hypercapnia. This can be an extremely helpful in the rapid workup of altered mental status and many other common presenting conditions.

3. How accurate do I need my PCO2 value to be?

If the answer to this question is “not that accurate” then a VBG is probably fine. Having a rough estimate of PCO2 levels is usually adequate for the management of mild-moderate DKA, COPD exacerbations, and many other conditions managed in the ED. While a PvCO2 value of 18 mmHg or 75 mmHg may not exactly correlate with what you find on a PaCO2, they are abnormal enough to give you a good general sense of things.

If you are interested in performing a more refined blood gas analysis such as determining the chronicity of a respiratory acidosis, measuring shunt fraction, or accurately quantifying a hypercapnic patient’s true PCO2 then you probably need an ABG. As noted above, the correlation between PaCO2 and PvCO2 is often poor.

4. Am I assessing oxygenation?

At times, obtaining a reliable SpO2 can challenging especially in patients with PAD, scleroderma, or shock. If you need an accurate assessment of oxygenation then you need an ABG. PvO2 values do not correlate well at all with PaO2.

5. Is my patient in shock?

As noted above, VBGs are much less accurate in shock. Unfortunately, this is where we are often most interested in frequent blood gas analysis. In the ED, I think ABGs are most useful (and underused) in critically ill acidotic patients who may or may not have appropriate respiratory compensation. This determination is hard to make on clinical grounds alone (i.e. the signs of early respiratory muscle fatigue can be subtle) and identifying fatigue may well change your management (pushing you to earlier NIV or mechanical ventilation). I would hesitate to solely rely on VBGs in this setting especially for patients in overt shock.

A few other points:

I do think the risks of an ABG as stated above and in other reviews (for example, https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/vbg-versus-abg/) are overstated. A competent clinician should be able to obtain an ABG from a radial artery in a matter of seconds. If there are any concerns regarding anatomy or first stick accuracy, the use of a vascular ultrasound probe can remove any guess work from finding the best arterial access site. ABGs do require an extra needle stick for patients so clinicians should be discerning about their use. However, if one is indicated they shouldn’t be avoided for fear of causing a pseudoaneurysm or major bleeding. Compared to innumerable other invasive procedures and diagnostic tests performed in the ED, ABGs are pretty benign. For some reason, they are still frequently described like thoracotomies.

Remember the following rough corrections

Venous pH is 0.03 lower than arterial pH (venous pH 7.27 = arterial pH 7.3)