Author: Gabby Alzadeh, MD (EM Resident Physician, PGY-1, NUEM) // Edited by: Kory Gebhardt, MD (EM Resident Physician, PGY-4, NUEM) // Expert Commentary: Lia Bernardi, MD & Magdy Milad, MD MS

Citation: [Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Alzadeh G, Gebhardt K (2016, May 17). Ovarian Hyperstimulation: Not Your Average Cyst. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bernardi L & Milad M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/ovarian-hyperstimulation

The Case

A 26 year old female G0 with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) undergoing fertility treatments presented with achy, diffuse abdominal pain and progressive shortness of breath over the past several days. She also noted nausea, several episodes of vomiting, and increasing abdominal distention. Today she felt like she could not catch her breath which is what brought her into the emergency room. She denies any vaginal bleeding or discharge.

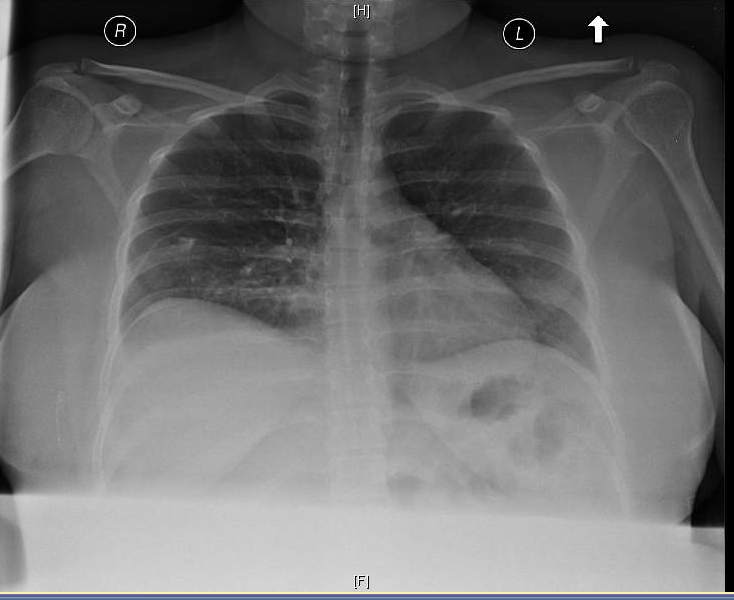

A bedside ultrasound was performed along with a chest x-ray (below). Labs notable for leukocytosis of 20.4 (ANC =15.7), Hb of 15.6, hct of 46.0, platelets of 561, Na 130, K 4.2, Cr of 0.81 (up from baseline of 0.54). Albumin was low at 2.6 and total protein low at 4.8. Serum quantitative HCG of 518.7. Her ECG demonstrates sinus tachycardia. There is troponin elevation. A diagnosis of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) was suspected and gynecology was consulted for admission.

Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

Approximately 1-2% of all live births in the United States are as a result of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), which includes procedures such as fertility medication, artificial insemination, IVF and surrogacy. Pregnancies resulting from assisted reproduction are more complicated, with higher rates of ectopic, heterotopic and multifetal pregnancies, in addition to higher rates of abortions and premature deliveries. Higher rates of maternal disease such as preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus, bleeding, anemia are also present. Other complications include venous thromboembolism (VTE) as well as OHSS.

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of women using ART are under the age of 35, with 57.7% of users being under the age of 37. Use of ART has almost doubled in the past 10 years, resulting in an increase in complications as well as multiple infant births.

Incidence of OHSS as a complication of ART by severity

Mild (20-33%)

Moderate (3-6%)

- Severe (0.1-2%)

Risk factors: for OHSS

Prior OHSS

Exaggerated ovarian response

- PCOS

Pathophysiology: Enlarged ovaries + abdominal distention + vascular permeability

In the normal ovulatory cycle, the hypothalamic-pituitary- ovarian feedback loop limits follicle recruitment leading to selection of a single follicle that ovulates in response to the LH surge. In OHSS, this feedback loop is disrupted, via exogenous gonadotropin, leading to an exaggeration of the physiologic process. The most high risk time is after administration of hCG as the final trigger of oocyte maturation. hCG has six to seven times the biological activity of endogenous LH. Complications from OHSS can be life threatening and include torsion, VTE, abdominal compartment syndrome, ARDS, cardiac tamponade, renal failure, and death (usually secondary to hypovolemia, hemorrhage and thromboembolic events). The flow chart below demonstrates the development of this process:

Classification

ED Evaluation

- CBC: anemia vs. bleeding complication vs. hemoconcentration

- Chemistry panel: creatinine elevation, electrolyte abnormalities

- LFTs, DIC panel, ECG if suspect severe or critical

- CXR & comprehensive bedside ultrasound

- Consideration of pulmonary embolism work up if respiratory complaint without identified etiology

- Consideration of ovarian torsion if significant lower abdominal pain given these patients are at high risk

Treatment

Treatment is mostly supportive. Your main goal should be to focus on correcting the underlying electrolyte and fluid status abnormalities. Be sure to avoid diuretics. These patients may appear volume overloaded however they are often intravascularly deplete. Specific therapies should be considered based on the patient’s other symptoms related to OHSS.

- Tense ascites and/or severe orthopnea: Paracentesis

- Symptomatic hydrothorax: Thoracentesis

- Acute Respiratory distress: Oxygen therapy and positive pressure ventilation

- Risk factors for VTE: Prophylactic anticoagulation

Disposition

Patient’s presenting with mild to moderate symptoms can usually be sent home with close follow up. These women should:

- Monitor for:

- Worsening abdominal pain

- Increased abdominal girth

- Weight gain > 1 kg/day

- Decrease in urine output

- Stay well hydrated

- Limit physical activity

Patient’s with severe symptoms should be admitted. Some characteristics and symptoms to consider for admission:

- Hct >45%, WBC >25,000, Cr >1.6, electrolyte imbalance, abnormal LFTs

- Oliguria/anuria, severe abdominal pain & vomiting

- Dyspnea/tachypnea, hypotension, dizziness, and/or syncope

You should consider thromboembolic prophylaxis (in consultation with obstetrics) when women have 2-3 of the following risk factors (hospitalized or managed as outpatient):

- >35 yo

- Obese

- Immobility

- Personal/family history of thrombosis

- Thrombophilia

- Pregnancy

Case resolution

The patient was admitted with moderate to severe OHSS (hemoconcentration, severe abdominal pain, emesis, tachypnea, hyponatremia, and oliguria) and was started on lovenox as she was obese and pregnant. A foley was placed for strict UOP monitoring. Tachycardia improved with fluid resuscitation, electrolytes normalized and Cr returned to baseline. She was discharged home 2 days after admission with dramatic symptomatic improvement.

Take Home Points

- The pathophysiology of OHSS is driven by a disruption of the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian feedback loop, ultimately leading to impairment of capillary beds (via systemic VEGF) and significant fluid shifts, resulting in edema, ascites, hydrothorax, pericardial effusion and significant intravascular depletion.

- The complications of OHSS include VTE, ovarian torsion, intravascular depletion, life threatening fluid shifts and significant end organ damage, all of which should be addressed and ruled out on presentation to the emergency department.

- Treatment of OHSS is mostly supportive and the goal in the emergency department is to correct underlying electrolyte and volume issues and target additional specific therapies to patient symptoms and physical exam findings.

- Disposition of these patients should be based on symptoms and lab findings in conjunction with their obstetrician to ensure appropriate follow up plan.

Expert Commentary

Ovarian hyperstimulation (OHSS), which is a potentially life-threatening iatrogenic complication of assisted reproductive technologies, is the most common complication of IVF. Mild OHSS can lead to enlarged ovaries, abdominal distention, and mild GI symptoms that can typically be managed as an outpatient. However, severe OHSS may result in massive ovarian enlargement, ascites, hydrothorax, renal failure, acute respiratory distress, stroke and death. While previous history and age are important risk factors, the presence of PCOS increases the risk 5-fold to as high as 25 percent.

Two clinical forms of OHSS exist with the early onset form occurring after administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and the late onset form occurring due to hCG secreted during pregnancy. The major cause of OHSS is the use of hCG as part of the final phases of ovarian stimulation for IVF. The administered hCG has LH-like properties that may persist for up to a week after administration and result in an excessive ovarian stimulation and occurrence of OHSS. Administration of hCG may result in a falsely positive serum hCG level when a patient presents to the emergency department within 8 days of egg retrieval.

Many strategies have been employed in an attempt to reduce OHSS including alternatives to hCG such as GnRH agonist ‘triggering’, in vitro maturation, dopamine agonists, IV albumin, metformin, and cancelling the IVF stimulation. Given that OHSS can develop or worsen if a patient becomes pregnant due to the rise in hCG, another prevention strategy is to cryopreserve embryos and proceed with a frozen embryo transfer once the ovaries have normalized in size. Avoiding embryo transfer in a patient with OHSS allows rapid resolution of symptoms approximately 2 weeks after egg retrieval coincident with menstruation. Most recently, Kisspeptin-54 underwent an open-label RCT in England eliminating the risk of OHSS with high pregnancy rates.

Presenting symptoms of OHSS may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distension and rapid weight gain. More severe OHSS may present with tense ascites, oliguria, tachypnea and/or chest pain. If a patient who recently underwent controlled ovarian hyperstimulation presents to the ED with these symptoms, it is critical to consider OHSS as an etiology. The differential diagnosis also includes ovarian torsion, ruptured ovarian cysts, post-procedure hemoperitoneum, severe constipation, or poorly controlled postoperative pain. Although rare, an injury to the bowel or urinary tract should also be on the differential. Even if a woman presents a week or later after oocyte retrieval with these symptoms and her pregnancy test is positive, she may also have OHSS. Other complications of early pregnancy such as ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion or hyperemesis gravidarum should be ruled out. In addition, in a woman presenting with cardiopulmonary symptoms, a pulmonary embolism must be considered as these can occur in the setting of OHSS due to hemoconcentration and elevated estradiol that results from controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, even if the patient does not have OHSS.

Women who present to the ED with symptoms of OHSS should have laboratory testing performed with a complete blood count, electrolytes, serum hCG level, urine specific gravity and renal/liver function tests. An abdominal ultrasound should be performed with care taken to avoid trauma to the enlarged ovaries. A pelvic exam is absolutely not necessary, is poorly tolerated and may provoke cyst rupture. A DIC panel can be considered in some cases depending on the clinical presentation. If cardiopulmonary symptoms are present, an ECG, chest x-ray and chest CT may also be required.

Many patients who experience mild OHSS undergo outpatient evaluation and management and never present to the ED or require inpatient care. However, if a patient is profoundly hemoconcentrated or has significant pulmonary or GI symptoms, hospital admission is often necessary. The goal of treatment in the ED includes serial clinical and laboratory evaluations until the patient is stable for outpatient management or admission to the appropriate inpatient service. In addition, an immediate goal is correction of hypovolemia, hypotension, oliguria, and electrolyte abnormalities. Thus, fluid resuscitation is a priority (generally a bolus of normal saline followed by maintenance fluids to avoid overload but maintain urine output >20-30 mL/hr). Goals of inpatient hospitalization also includes hydration to prevent ATN, maintaining electrolytes, anti-emetics, DVT chemoprophylaxis and regular (every day or other day) paracentesis or culdocentesis for temporary relief of tachypnea/dyspnea. IV albumin and dopamine agonists are used but without much evidence. Once committed to DVT chemoprophylaxis, it should be maintained after discharge for up to 8 weeks when ovarian enlargement starts to wane. Evidence of resolution of OHSS includes improvement in clinical symptoms, diuresis, and normalization of laboratory tests.

Magdy Milad, MD, MS

Albert B. Gerbie Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology; Vice Chair of Education; Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine

Lia A. Bernardi, MD

Fellow, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology & Infertility; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology; Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine

Other Recent Posts

References

- Binder H, Dittrich R, Einhaus F, et al. Update on ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Part 1--Incidence and pathogenesis. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2007; 52(1):11-26.

- Delvigne A. Symposium: Update on prediction and management of OHSS. Epidemiology of OHSS. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009; 19(1):8-13.

- Fábregues F, Balasch J, Ginès P, et al. Ascites and liver test abnormalities during severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999; 94(4):994-9.

- Grossman LC, Michalakis KG, Browne H, et al. The pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: an unrecognized compartment syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2010; 94(4):1392-8.

- Papanikolaou EG, Tournaye H, Verpoest W, et al. Early and late ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: early pregnancy outcome and profile. Hum Reprod. 2005; 20(3):636-41.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008; 90(5):188-93.

- Rutkowski A, Dubinsky I. Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome: Imperatives for the Emergency Physician. J Emergency Medicine.1999; 17(4):699-72.

- Soave I, Marci R. Ovarian stimulation in patients in risk of OHSS. Minerva Ginecol. 2014; 66(2):165-78.