Written by: Jordan Maivelett, MD (NUEM ‘20) Edited by: Andrew Berg (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Tim Loftus, MD, MBA

Introduction

Sepsis. As emergency medicine physicians, we are all quite familiar with the term and its tenets. We all know that early goal directed therapy, including early antibiotics, is an important part of sepsis management and ensuring the best possible outcomes for our patients. You need look no further than international guidelines and subsequent quality benchmarks to see the strong emphasis on timely care. For example, regarding antibiotics, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines have a clear recommendation:

It makes sense that early antibiotics are important, but just how important is the timing itself? If we miss the one hour recommendation after “recognizing” sepsis, how does that impact the patient, and is that impact clinically significant? Specifically, how does the timing of antibiotic administration affect mortality in sepsis? Numerous studies have tried to answer that exact question, and I wanted to take the time to review the evidence available to us today.

What we know so far

Kumar et al published one of the first major studies that examined the effects of antibiotic timing on mortality, specifically in patients with septic shock, in 2006. [1] This retrospective study included 2154 patients with septic shock and analyzed the impact of hourly delays in antibiotics on in-hospital mortality. Septic shock was defined as recurrent or persistent hypotension despite fluid resuscitation, and the timing of antibiotics was measured from the onset of said shock. The results were powerful, showing that for each hourly delay after onset of septic shock, in-hospital mortality increased by an average of 7.6% per hour. [1] It is important to note that this was an absolute increase in mortality, and a rather large one at that. Not surprisingly, prompt antibiotic administration in patients with septic shock is paramount. But what about patients with sepsis or severe sepsis who are not in shock?

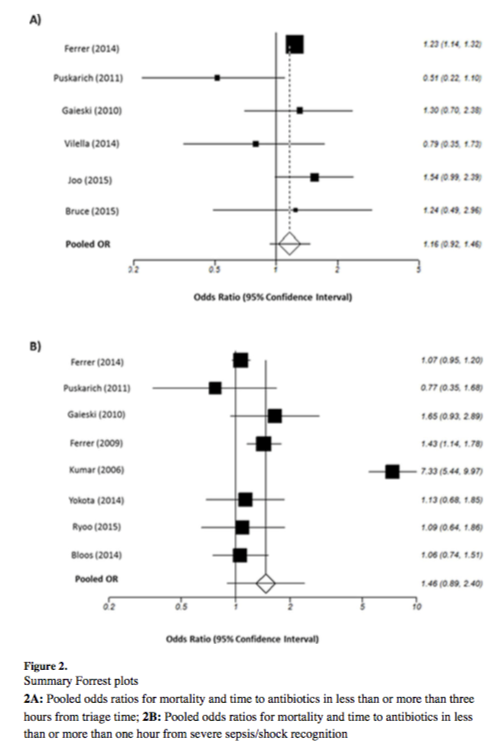

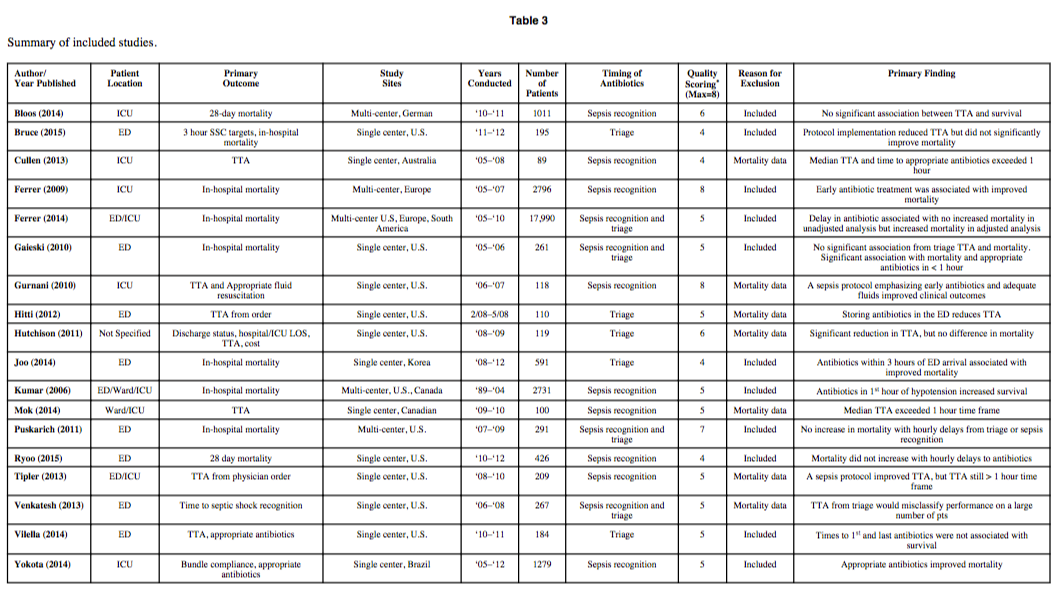

Many studies have attempted to answer that question, with mixed results. One of the largest and most comprehensive of these studies was a meta-analysis published by Sterling et al in 2015. [2] The meta-analysis included 11 studies totaling 16,178 patients and sought to study the effect of antibiotic timing on in-hospital mortality based on two specific timings: 1) Antibiotic administration less than or greater than three hours from ED triage, and 2) Antibiotic administration less than or greater than one hour from recognition of severe sepsis/septic shock. The latter scenario was included to address the one-hour target recommended in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines that was previously mentioned. The study also included an analysis of the effect of delayed antibiotics on mortality in hourly intervals after severe sepsis/septic shock recognition. Interestingly, the study showed no statistical difference in mortality between any of the time points studied. The results are best visualized in Figure 3 from the article, which shows the pooled odds ratios for the two major time points studied. Also included is a summary table that shows the included studies and their associated primary outcomes:

As you can see, the results of the included studies were mixed, with the overall meta-analysis showing no significant difference in in-hospital mortality based on time of antibiotic administration. [2] However, it is worth noting that some of the individual studies demonstrated significance, and the overall trend was toward improved mortality with earlier antibiotics despite no demonstrable significance when pooled together. As previously mentioned, the authors also examined the impact on mortality for each hourly delay after one hour of severe sepsis/septic shock recognition. The pooled odds ratios trended toward improved mortality with earlier antibiotics but again were not statistically significant. [2]

In contrast, Liu et al published a large retrospective study in 2017 that showed significant differences in mortality based on antibiotic timing. [3] Specifically, the study included 35,000 patients from 2010 to 2013 and analyzed the impact of antibiotic timing on in-hospital mortality in patients with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Septic shock was defined as patients needing vasopressors or an initial lactate greater than four. Severe sepsis was defined based on signs of end organ dysfunction, including laboratory abnormalities, one or more episodes of hypotension, or need for mechanical or noninvasive ventilation. The remaining patients were included in the sepsis group. The timing of antibiotic administration was measured from initial ED registration. The results were significant, with absolute increases in in-hospital mortality of 0.3%, 0.4%, and 1.8% per hour of delay in antibiotic administration in the sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock groups, respectively. [3] Although this is a single, retrospective study and not a meta-analysis, it involves a much larger number of patients in comparison to the Sterling meta-analysis. It is also worth noting that said meta-analysis, though totaling 16,178 patients, was unable to include all studies in each of its analyses, limiting its power.

Overall, the current evidence for timing of antibiotic use in sepsis is mixed, with some studies showing a statistically significant benefit in mortality reduction with early antibiotic use, while others showed a non-significant trend suggestive of the same. Antibiotics are clearly an important part of sepsis management, with earlier antibiotics appearing to be most important in patients with septic shock. However, the data are currently insufficient to specify an exact time point for initiation of antibiotics in septic patients.

So where do we go from here?

Although the data for early antibiotic use are mixed, the signal is clearly suggestive of improved mortality with earlier antibiotic use, and there are future studies that plan to take this to its logical extreme: pre-hospital antibiotics given by EMS. It will be interesting to see the results of such studies and how they juxtapose with the potential harm of unnecessary antibiotics. Of note, this latter concept of the harm of antibiotics given to patients with SIRS criteria who are later found to not have sepsis was not included in the aforementioned articles. Most of the above studies identified patients with sepsis in retrospect, separated them from those that were determined to have an inflammatory or viral process, and studied timing of antibiotics in the septic patients alone. But how did the administration of unnecessary antibiotics affect the non-septic patients? Data exist regarding the impact of antibiotic overuse on a larger scale, hence pushes for antibiotic stewardship and efforts to limit antibiotic resistance. However, patient centered outcomes and how they are affected by the possible increase in antibiotic misuse as we push for earlier antibiotics in sepsis management remains unclear. This is worth including in future analyses, as we need to be able to balance the benefits of giving early antibiotics with the potential risks of inappropriate antibiotic use in the undifferentiated patient.

For example, say it is the peak of flu season, and you have a febrile, tachycardic, normotensive patient with an influenza-like illness that you have yet to see. The patient is currently undifferentiated and could have a viral, bacterial, or inflammatory process. Do you give broad spectrum antibiotics up front, after seeing and examining the patient, or after you have performed an infectious work-up? Even with the above data at our disposal, I think this question is still hard to answer, practice patterns vary, and the only true answer is “it depends.” It is a decision to be made on a case-by-case basis, is dependent on the patient’s presentation and co-morbidities, and the risk of delaying antibiotics must be balanced with the potential harm of giving unnecessary antibiotics. A potential harm that is still relatively unclear.

As of now, all we can say is that the data are mixed. There is a signal suggesting early antibiotics improve mortality in sepsis, and this signal is larger in patients with septic shock. However, not all studies have shown significance, and there is no obvious time point to target based on the current data. Early antibiotics appear to be better, but again, this is for patients with “recognized” sepsis and not necessarily all undifferentiated patients who meet SIRS criteria.

Take Home Points

Current guidelines and quality measures stress the importance of timely antibiotics after recognition of sepsis.

Data on antibiotic timing in sepsis are mixed. Early antibiotics seem to affect mortality in sepsis, and this effect appears larger in patients with septic shock. If the patient is hypotensive and there is concern for infection, antibiotics are warranted.

The risks of inappropriate antibiotic use in the undifferentiated, potentially septic patient and their affect on patient outcomes remain unknown. This warrants study, as the push to give earlier antibiotics risks increasing the rate of unnecessary antibiotic administration.

Expert Commentary

Thank you to Doctors Jordan Maivelett and Andrew Berg for this well-written and thoughtful overview of the challenging scenario regarding appropriate timing of antimicrobial therapy in sepsis.

Overall, I would agree with the Take Home Points as espoused by the authors yet would like to highlight a few important considerations:

First, and perhaps most importantly, is the recognition that many of the available evidence is retrospective in nature, often analyzing administrative databases collected for other reasons (i.e. not to study outcomes in sepsis). The study by Liu et al as referenced above falls into this category (so does the notorious Kumar study, by the way). It is important to understand the inherent limitations in these studies - often, there is very limited information on exact confirmation that there even was an infection, the adequacy of antimicrobial selection, and details concerning source control. Further, be mindful of studies that adjust data to a large degree. The Liu study is a good example of this as well as the Ferrer 2014 study. Additionally, roughly 20% of the time, patients initially thought and treated as septic will be found to have no identifiable source or concern for infection when all said and done (Heffner’s study highlights this; even Kumar’s study had ~20% of pts without evidence of infection). Further, in the Kumar study, a significant cohort of patients were excluded in whom antimicrobials were administered prior to the development of hypotension. Fascinatingly, these patients actually did much worse than those who developed hypotension and subsequently were administered antimicrobials. Who would have hypothesized that?

Second, many prospective studies [2-3,5,7-9] including several that were part of Sterling’s SRMA-- do not conclude that early antimicrobials improve survival. One study assessed the mortality difference between those administered antimicrobials empirically and those in whom antimicrobials were delayed until objective microbiological confirmation of infection -- a practice which actually was associated with a significant survival benefit. [7] The MEDUSA study did find that delaying definitive source control (i.e. surgery or CT-guided drainage) >6 hours was associated with increased mortality. An additional prospective study even identified that inadequate antimicrobials were given about 33% of the time, and yet 30d mortality was identical. [4] An important conclusion from the authors was that “outcome is determined primarily by patient and disease factors.”

The authors mention trials analysing the prehospital administration of antimicrobials, a practice akin to mobile stroke units, pre-hospital TPA administration, and the theoretical (but unproven?) benefit of this practice. The PHANTASi trial was a prospective RCT looking at prehospital antibiotic administration. [1] In short, it did not improve survival compared to usual care. Unfortunately, this study was thought to be impacted by several confounders limiting its impact on practice.

Be wary of time to intervention studies. These are clinically important and impactful research questions, but many clinicians have difficulty in extrapolating the results to pathophysiologic mechanisms of disease. In other words, time zero of infection is often different - by a significant degree - than time of ED presentation as well as recognition of sepsis. Expecting an hourly linear relationship between mortality and antibiotics seems dubious.

Triage-based metrics perform poorly, as many patients with sepsis are misclassified initially and many patients don’t even meet diagnostic criteria until well after ED/hospital arrival. [12-13]

Bottom Line

Sepsis survival has increased over the past two decades, from the early phases of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and the Barcelona Declaration, to Rivers and EGDT, to ProCESS/ProMISe/ARISE and beyond. Largely, this seems to result from structured, multidisciplinary resuscitation, rapid approach to the recognition, diagnosis, and care coordination of this patient population. Given the complexity of what we understand as the pathophysiology of sepsis, it seems unlikely that a single point in time intervention would have such a profound and pivotal impact on survival. Please don’t delay appropriate antimicrobial therapy particularly in the face of critical illness. Although I’m not quite at the Mervyn Singer end of the spectrum (“I have yet to be convinced by the prima facie argument that antibiotics make a huge difference to outcomes”) [11], but be mindful of inappropriate, harmful empiric broad spectrum antimicrobials to beat a clock when the diagnosis is still in question. At the end of the day, retrospective analyses should generate hypotheses, not dictate policy and value-based quality metrics.

Further Reading

Alam et al. Prehospital antibiotics in the ambulance for sepsis: a multicentre, open label, randomised trial. Lancet 2018;6(1):40-50. (PHANTASi trial)

Bloos et al. Impact of compliance with infection management guidelines on outcome in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective observational multi-center study. Crit Care 2014;18:R42. (MEDUSA)

de Groot et al. The association between time to antibiotics and relevant clinical outcomes in emergency department patients with various stages of sepsis: a prospective multi-center study. Crit Care 2015;19:194.

Fitzpatrick et al. Gram-negative bacteraemia: a multi-centre prospective evaluation of empiric antibiotic therapy and outcome in English acute hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:244–251.

Kaasch et al. Delay in the administration of appropriate antimicrobial therapy in Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a prospective multicenter hospital-based cohort study. Infection 2013;41: 979–985. (preSABATO study)

Heffner et al. Etiology of illness in patients with severe sepsis admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(6):814-820.

Hranjec et al. Aggressive versus conservative initiation of antimicrobial treatment in critically ill surgical patients with suspected intensive-care-unit-acquired infection: a quasi-experimental, before and after observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12: 774–780.

Puskarich et al. Association between timing of antibiotic administration and mortality from septic shock in patients treated with a quantitative resuscitation protocol. Crit Care Med 2011;39: 2066–2071. (EMSHOCKNET).

Ryoo et al. Prognostic value of timing of antibiotic administration in patients with septic shock treated with early quantitative resuscitation. Am J Med Sci 2015;349:328–333.

Seymour et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. NEJM 2017;376:2235-2244. (the NY State Data)

Singer M. Antibiotics for sepsis: does each hour really count, or is it incestuous amplification? Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2017;196(7):800-802.

Venkatesh et al. Time to antibiotics for septic shock: evaluating a proposed performance measure. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31(4):680-683.

Villar et al. Many emergency department patients with severe sepsis and septic shock do not meet diagnostic criteria within 3 hours of arrival. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64(1):48-54.

Timothy M Loftus, MD, MBA

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Assistant Medical Director

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Kumar et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006 Vol. 34, Issue 6.

Sterling et al. The Impact of Timing of Antibiotics on Outcomes in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta- analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015 Vol. 43, Issue 9: 1907–1915.

Liu et al. The Timing of Early Antibiotics and Hospital Mortality in Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017 Vol. 196, Issue 7: 856–863.