Written by: Vidya Eswaran, MD (NUEM PGY-3), Zach Schmitz, MD (NUEM PGY-2), Abiye Ibiebele, MD (NUEM PGY-2) Edited by: Michael Macias, MD and Arthur Moore, MD (NUEM Alum ‘17) Expert commentary by: John Bailitz, MD

Introduction

I’ve been suffering in that waiting room for hours!

That worthless tech stabbed me with a needle ten times!!

If you don’t give what I want right now, I am going to hurt someone!!!

Every emergency physician can recall a time when they hear these words or similar phrases echoing throughout the Emergency Department (ED). As a patient becomes increasingly agitated, nearby staff and visitors become distracted, and ultimately concerned about everyone’s safety. Emergency Physicians can help restore the calm amidst the chaos by recognizing subtle clues and intervening early.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, those who work in the healthcare sector had three times the rate of illness and injury from violence compared to all private industries [1]. In a survey of emergency medicine residents, 65.6% reported an experience of physical violence by a patient, 96.6% reported verbal harassment from a patient, and 52.1% reported sexual harassment by a patient. Often these patients were under the influence of drugs or alcohol, had a psychiatric disease, or an organic cause of their agitation, such as dementia [2]. In Australian emergency departments, 3 of every 1000 ED visits are associated with an episode of violence or acute behavioral disturbance [3].

When violence by a patient is imminent or has already occurred, the patient requires immediate restraint by either chemical or physical means [4]. ACEP guidelines for patient restraints supports the careful and appropriate use of restraints or seclusion if “careful assessment establishes that the patient is a danger to self or others by virtue of a medical or psychiatric condition and when verbal de-escalation is not successful [5].” Verbal “de-escalation techniques aim to stop the ascension of aggression to violence, and the use of physically restrictive practices, via a range of psychosocial techniques [6],” and should be tried before one simply grabs “5 and 2.”

Clinical Approach to Agitation

How do you determine which patients would benefit from verbal de-escalation?

Look for the agitated patient, the one who has an angry demeanor, using loud and aggressive speech, seems tense and is grasping their bed rails or clenching their fists, the one who is pacing or fidgeting [4]. These patients are in the pre-violent stage, and may have the potential to be successfully talked down. If a patient has already engaged in violent acts, it is too late to intervene with verbal de-escalation methods.

What principles should be used to assist with verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient?

In 2012 the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry offered a consensus statement on verbal de-escalation and created ten key domains to guide care of agitated patients. These domains offer a great framework for how to approach the agitated patient before the situation escalates [7].

Domain 1: Respect the patient’s and your personal space. First and foremost in any patient encounter, especially one with an agitated patient, is your safety. Aim to keep at least 2 arms lengths distance between you and the patient. This offers you room for your own personal safety, and is seen as non-confrontational and non-threatening in the eyes of the patient. Ensure that both you and the patient have an unobstructed pathway to the exits and that you do not stand in the way of the patient’s path to leaving the room.

Domain 2: Do not be provocative. The majority of our interpersonal interactions is communicated not by the words we say, but how we say them. Our body language is crucial and we must be mindful of it when attempting to calm a patient. Keep your hands visible and at ease, bend your knees slightly, avoid excessive direct eye contact and approach your patient from an angle instead of head-on. These positions convey a non-threatening demeanor.

Domain 3: Establish verbal contact. The first person to interact with the patient should be the one who leads the verbal de-escalation. Introduce yourself and tell the patient your role and orient them to their surroundings. Then, ask the patient what they would like to be called. This gives the patient the impression that you believe he or she is important and has some control over the situation.

Domain 4: Be concise and caring. Use short sentences and simple vocabulary to get your point across. Give your patients time to process what you have said and to respond before continuing. You should be prepared to repeat your message multiple times until your patient understands.

Domain 5: Identify wants and feelings. In order to provide empathetic care, you must understand your patient’s perspective. Listen carefully to what your patient says to pick up clues and respond to their desires. One tactic is to say “I really need to know what you expected when you came to the ED today. Even if I can’t provide it, I would like to know so that we can work on it together.”

Domain 6: Listen closely to what the patient is saying. This is closely related to Domain 5. Practice closed loop communication, repeat what the patient has told you to ensure you have understood them correctly.

Domain 7: Agree, or agree to disagree. Look for something that you can agree with in what the patient is saying. “I agree, waiting can be frustrating” or “Yes, I understand that the nurse has stuck you three times.” However, if you can’t find something to agree with the patient about, do not lie - agree to disagree.

Domain 8: Lay down the law and set clear limits. Draw a line which the patient must not cross. Let him or her know that harming himself or others is unacceptable and will result in specific consequences (seclusion, arrest, prosecution). This should not be portrayed as a threat, but rather be conveyed in a respectful manner. You can preface it with “Your behavior is making our staff uncomfortable and that makes it difficult for us to help you.”

Domain 9: Coach the patient on how to stay in control. Give the patient tactics they can use to help de-escalate the situation. “If you sit down we can discuss why you are here.”

Domain 10: Be optimistic and provide hope that the patient will be able to get to a favorable outcome. “I don’t want you to stay here longer than you need to. Let’s work together to help you get out of here feeling better.” Be sure to debrief with the patient and staff after the de-escalation, so that there is a strategy in place if this were to happen again.

Other strategies include recruiting the patient’s friends and family to help and to employ the three Fs technique - feel, felt, found [8]. “I understand that you feel X. Others in the same situation have felt that way to. Most have found that doing Y can help [4].”

Think of verbal de-escalation as a procedure just like intubations or central lines - with practice, comes mastery. Rehearse what you plan to say, and do mental run-throughs of de-escalations. Watch and learn from others who do this well. The English Modified De-Escalating Aggressive Behaviour Scale (EMDABS) is a validated tool you can use to assess your performance during de-escalations [9].

Summary

Unfortunately, physical and chemical restraint of the severely agitated patient is sometimes needed to protect ED staff, visitors, and the patient themselves. [10,11]. But by recognizing subtle signs of agitation early, we can often utilize effective verbal-de-escalation techniques to create safety for everyone!

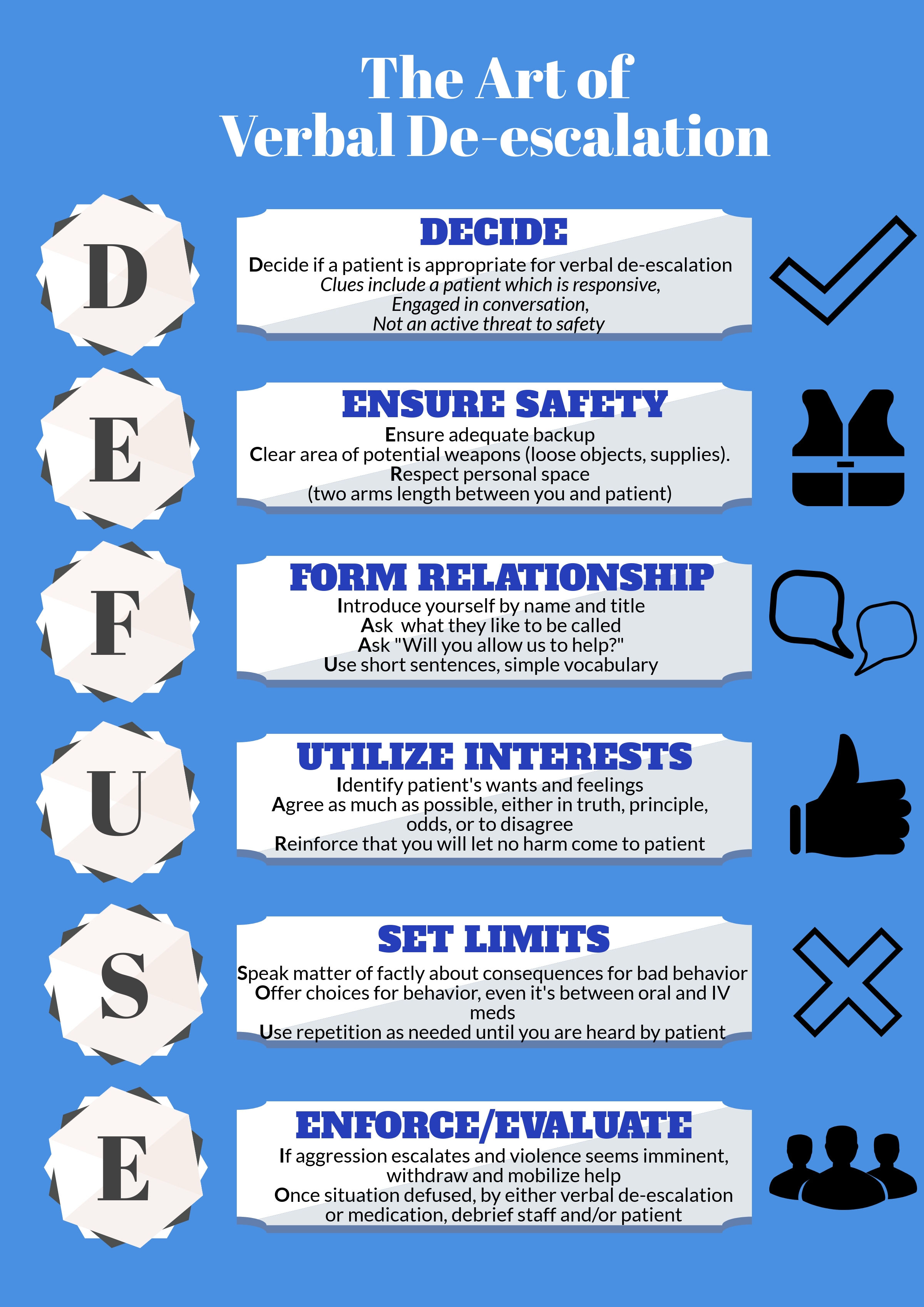

Check out our infographic for an easy to use mnemonic which summaries key points.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this outstanding review of an incredibly important topic topic with tragically little supporting evidence to guide best practice. Colleagues and patients in multiple different practice settings throughout Chicago have repeatedly taught me several key pearls and pitfalls when dealing with the agitated patient.

For the mildly agitated patient, always open with an apology that empathically validates the patient or visitor emotions. “I am very sorry that you have been suffering in the waiting room for so long. That must have been very frustrating. My sincere apologies.” Never reply with a sharp justification or any explanation. Just acknowledge their frustration, own it, and the patient will quickly move past the emotion. Often times, this first connection forms the foundation of a healthy patient physician relationship and even a thank you letter to your ED Director.

For the patient whose agitation is escalating despite appropriate efforts by trained ED staff, call security or hit the duress button for back up before stepping into any potentially risky situation. If you are single covered at 3 AM, you cannot become another patient. When help arrives, ask security to simply stand in the hallway as you begin your DEFUSE techniques. Politely but purposefully excuse inexperienced staff members who have themselves become agitated and entered into a shouting match with patients or visitors. Always keep your own emotions in check and debrief with everyone involved after each learning opportunity.

Finally, when the sedation is needed for patient and staff safety, assemble your team, and proceed with the utmost professionalism. As a physician, you have no role in the physical restraint process unless absolutely necessary. Your security staff has been trained in proper physical restraints while chemical sedation catches up with the dangerous patient. If the patient is acutely agitated without concerns for respiratory depression, utilize 5 mg of Haldol + 5 mg of versed instead of the traditional 2 mg of Ativan. Everyone in the ED will become safer more quickly and the patient will wake up more rapidly for reassessment.

Just remember, “Patients First” always starts with everyone’s safety first!

John Bailitz, MD

Program Director, Northwestern Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Eswaran V, Schmitz Z, Ibiebele A, Macias M, Moore A. (2019, March 4). Verbal De-escalation in the ED. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/verbal-deescalation

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Requiring Days Away From Work, 2014.Bureau of Labor and Statistics News Release. 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh2_11192015.pdf

Schnapp et al. Workplace Violence and Harassment Against Emergency Medicine Residents, WJEM 2016: 17(5) 567-573. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/pmc/articles/PMC5017841/pdf/wjem-17-567.pdf

Downes et al. Structured team approach to the agitated patient in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia (2009) 21, 196-202 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/doi/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01182.x/epdf

Moore, G and Pfaff, J. Assessment and emergency management of the acutely agitated or violent adult.Up to Date. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/contents/assessment-and-emergency-management-of-the-acutely-agitated-or-violent-adult?source=search_result&search=Assessment%20and%20emergency%20management%20of%20the%20acutely%20agitated%20or%20violent%20adult&selectedTitle=1~150#H17

ACEP Policy on Patient Restraints https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Use-of-Patient-Restraints/

Price et al. Learning and performance outcomes of mental health staff training in de-escalation techniques for the management of violence and aggression. The British Journal of Psychiatry (2015) 206, 447-455 http://bjp.rcpsych.org.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/content/bjprcpsych/206/6/447.full.pdf

JS Richmond et al. Verbal De-escalation of the Agitated Patient: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health 2012: 13(1) 17-25. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/55g994m6

Nickson, C. De-Escalation. Life in the Fast Lane. 2014. http://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/de-escalation/

Mavandadi et al. Effective ingredients of verbal de-escalation: validating an English modified version of the ‘De-Escalating Aggressive Behaviour Scale’. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2016, 23, 357-368. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/doi/10.1111/jpm.12310/epdf

Weingart, S. Podcast 060 – On Human Bondage and the Art of the Chemical Takedown. EMCrit. 2011. http://emcrit.org/podcasts/human-bondage-chemical-takedown/

Nickson, C. Chemical Restraint. Life in the Fast Lane. 2014. http://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/chemical-restraint/