Written by: Patrick King, MD Edited by: Nery Porras, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: Anne Lambert Wagner, MD

TPA in Frostbite

Figure 1. What we would like to avoid (Cline et al.)

It’s an early Saturday morning, and EMS brings in one of your ED’s regulars – a schizophrenic, undomiciled gentleman named Jack who finds occasional work as a day laborer. You walk to bed three to greet Jack who is uncomfortable and shivering while nursing collects vitals. His chief complaint is hand and foot pain. You listen to him speak, but you jump right into a cursory exam as he does – and your heart sinks when you see the icy hard, cyanotic, mottled digits across all four extremities. You wonder what else you might be able to offer in addition to the standard cold injury approach we are taught as emergency residents, and you recall that the What’s New in Emergency Medicine section of UpToDate just recognized growing evidence for yet another off-label use for tPA: severe frostbite.

As we head into the winter months, emergency physicians will continue to see frostbite wreck a significant level of morbidity on our most vulnerable patients – patients who are undomiciled, suffering from addictions or mental illness, and those with preexisting conditions that limit blood flow to extremities (Zafren and Crawford Mechem). This post will address the theory, evidence, and logistics behind tPA utilization in severe frostbite.

The proposed efficacy of tPA in frostbite is related to cold-induced thrombosis. Endothelial damage is sustained both as a direct result of cold-related injury and exacerbated by reperfusion injury during the period of rewarming. During rewarming, arachidonic acid cascades promote vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, leukocyte sludging, and erythrostasis which further promote thrombosis throughout affected tissues. This process is compounded in instances of multiple freeze-thaw cycles (Cline et al).

Research on tPA in frostbite goes back years. In 2005, Twomey et al. demonstrated in an open-label study that technetium (Tc)-99m scintigraphy (i.e., nuclear bone scan) reliably predicts digits/limbs at risk for amputation. Historical control patients with no or minimal flow distal to radiographically identified “cutoff” points of ischemia on bone scans inevitably all required amputations. Untreated historical controls without flow cutoffs were more likely to retain digits. In contrast, 16 of 19 study patients with identified flow cutoffs responded to intra-arterial (IA) or intravenous (IV) tPA with an amputation rate of only 19% of at-risk digits. In 2017, Patel et al. showed a 15% amputation rate for severe frostbite in eight IA tPA patients compared to 77% in their control group.

Figure 2. Pre-tPA and Post-tPA using technetium (Tc)-99m scintigraphy bone scan (Twomey et al.)

While study results have been impressive in instances of small sample sizes such as the above, a paucity of evidence has prevented widespread utilization of tPA for frostbite use amongst emergency physicians. This year, however, What’s New In Emergency Medicine on UpToDate gave special attention to a 2020 systematic review of 16 studies by Lee and Higgins which wielded a sample size of 209 patients with 1109 digits at high amputation risk. The study, entitled “What Interventional Radiologists Need to Know About Managing Severe Frostbite”, ultimately demonstrated a 76% salvage rate amongst IA tPA (222 amputations amongst 926 digits) and 62% salvage rate in IV tPA (24 amputations amongst 63 patients). Importantly, the 16 studies are not randomized, though several such as Patel et al. and Twomey et al. utilize historical controls. There is also no direct comparison of IA vs. IV tPA, and for unclear reasons, the salvage rate for IA is in terms of digits salvaged out of those at risk while IV is expressed as a function of patients who required no amputations. Though there remains additional research to be done, UpToDate’s Frostbite authors Zafren and Crawford Mechem now give an overall grade 2C recommendation for tPA use in severe frostbite for patients otherwise at risk of life-altering amputations.

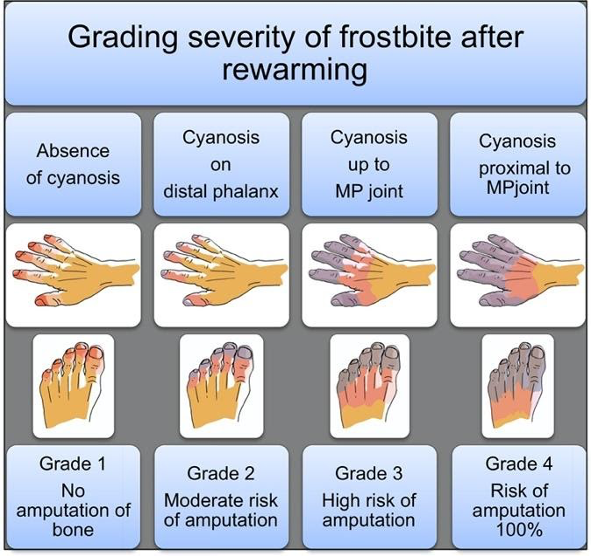

Figure 3. Grading severity of frostbite after rewarming (Cauchy et al.)

Figure 4. Grade 4 Frostbite, best seen in far right (Pandey et al.)

TPA utilization in frostbite is straightforward. UpToDate authors recommend tPA consideration for any patients with frostbite in multiple digits in a single limb, in multiple limbs, and/or in proximal limb segments who present within 24 hours of injury. The American Burn Association, which has its own guidelines (largely similar), recommends tPA for patients with cyanosis proximal to the distal phalanx after rewarming (i.e. grade 3 or 4). In more simple terms – injuries expected to be life-altering, as revealed following rapid rewarming, are likely to meet inclusion. Contraindications include general tPA contraindications as well as frostbite-specific considerations such as multiple freeze-thaw cycles which destroy tissue viability via repeated reperfusion injury as discussed previously. An additional frostbite-specific quandary with tPA use is the intoxicated frostbite patient, as substance abuse is a strong risk factor for frostbite, but intoxication can preclude tPA consent.

So you suspect you have a candidate – how do you proceed? Advice from UpToDate’s Zafren and Mechem is representative of many experts’ approaches. Early consultation with centers experienced in advanced frostbite therapeutics is recommended. General immediate frostbite care is undertaken on ED arrival, including 15-30 minutes rapid water bath rewarming at 37 to 39 degrees Celsius, at which point the tissue should change from hard and cold to more soft and pliable. Ensure adequate analgesia, as this rewarming process can be painful. Following rapid rewarming, the grade of frostbite can be assessed (fig. 2,3). Clinical suspicion is then confirmed via technetium (Tc)-99m scintigraphy (bone scan) or by angiography at centers with expertise in intra-arterial tPA use. Angiography is utilized only if IA administration is planned. UpToDate recommends IV tPA for most candidates given the ease of administration unless specific institutional protocol differs.

Specific UpToDate dosing regimen is as follows: “Give a bolus dose of 0.15 mg/kg over 15 minutes, followed by a continuous IV infusion of 0.15 mg/kg per hour for six hours. The maximum total dose is 100 mg. After tPA has been given, adjunct treatment can be started with IV heparin or subcutaneous (SC) enoxaparin. The dose of IV heparin is 500 to 1000 units/hour for six hours or targeted to maintain the partial thromboplastin time (PTT) at twice the control value. Enoxaparin can be given at the therapeutic dose (1 mg/kg SC).”

Additional research remains to be done on this topic. At this time, however, it is reasonable to give your patients – a hand – when it comes to severe frostbite. Consider tPA.

Expert Commentary

Background

Skin and soft tissue are readily susceptible to injury at either end of the temperature spectrum. With exposure to cold, unprotected tissues can readily become frostbitten and/or hypothermic (aka Frostnip); two distinct but often linked injuries. In the past, skin, limbs, and digits sustaining severe frostbite injury had predictable outcomes: sloughing or amputation. The only question was how long to wait to amputate. Essentially no progress was made in the treatment of frostbite until the early 1990’s when the development of a treatment protocol for frostbite patients was developed using thrombolytics to restore blood flow to damaged tissue.

Frostbite has two separate mechanisms to the injury itself. The initial insult is the cold injury that leads to direct cellular damage from the actual freezing of the tissues. Rewarming of the affected tissues leads to the second, a reperfusion injury resulting in patchy microvascular thrombosis and tissue death.

Figure 1. Frostbite

Frostbite Classification

First-degree frostbite: Superficial damage to the skin from tissue freezing with redness (erythema), some edema, hypersensitivity, and stinging pain.

Second-degree frostbite: Deeper damage to the skin with a hyperemic or pale appearance, significant edema with clear or serosanguinous fluid-filled blisters, and severe pain. Frostnip, first and second-degree frostbite will generally heal without significant tissue loss.

Third-degree frostbite: Deep damage to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Cold, pale, and insensate without a lot of tissue edema. Shortly after rewarming, edema rapidly forms along with the presentation of hemorrhagic blisters. Significant pain often occurs after rewarming.

Fourth-degree frostbite: All the elements of a third-degree injury with evidence of damage extending to the muscle, tendon, and bone of the affected area.

Figure 2. 1st and 2nd degree frostbite (left), 3rd and 4th degree frostbite (right)

Pre-hospital or Emergency Department Management

Determining the extent of frostbite injury starts with a detailed history regarding how the affected area appeared on presentation.

The history of a cold, white, and insensate extremity on presentation is consistent with severe frostbite injury (3rd and/or 4th-degree frostbite).

A severe frostbite injury requires emergent therapy with thrombolytics unless the patient meets one of the exclusion criteria.

If in question regarding the depth of the injury, a clinical exam can be supported by a vascular study as indicated. A digital Doppler exam is a simple and quick modality to further Clarify the diagnosis of severe frostbite.

Complete a primary survey to rule out any traumatic injuries.

Correct hypothermia (warm room, remove wet clothing & jewelry, warmed fluids, etc.)

If there are areas of frozen tissue rapid rewarming is preferred (see next section, rapid rewarming is associated with the best outcomes and salvage rates. However, never thaw until the risk of re-freezing has been eliminated. Patients undergoing freeze-thaw cycles do not respond to thrombolytics and are treated with standard supportive frostbite therapy.

Protect affected areas from further trauma with padding, splinting, and immobilization while transporting.

Keep the patient non-weight bearing to avoid incurring additional injury to frozen tissue (ice crystals) and/or disrupting blisters.

Elevate the affected extremities when able to decrease tissue edema.

Obtain a large-bore peripheral IV & start warmed fluids. Most patients will present with dehydration secondary to hypothermia and/or intoxication.

Avoid direct radiant heat to prevent iatrogenic burns to the cold tissue.

Update the patient’s tetanus status

Expect the patient to have increasing pain as the involved tissue is rapidly rewarmed. Pain management should include scheduled Ibuprofen (800 mg if no contraindication) to block the arachidonic cascade, gabapentin (nerve pain), and narcotics as needed.

Figure 3. Rewarming

Rapid rewarming

Circulating water bath when able. Put each affected area in its own water bath to avoid the tissue “knocking” against each other.

Document start & completion time

Try to keep the water temp at 104 ºF (40º C)

It will take 30-45 min for a hand or foot

If the patient has boots, socks, gloves, etc frozen to the skin do not force off. Submerge the entire area as part of the rapid rewarming process

Continue until frostbitten limb becomes flushed red or purple, and tissue soft and pliable to gentle touch

Air Dry

Avoid any aggressive manipulation to decrease tissue loss and injury

Elevate the affected areas to decrease swelling

Dress the affected areas with bulky padded dressings for transfer to avoid trauma to the areas

Avoid rewarming with a direct heat source (heat lamp, warm IV bag, etc.). This will lead to a thermal injury secondary to the lack of blood flow.

Rewarming will be associated with:

A return of sensation, movement, and possible initial flushing of the skin. The vessels in the case of severe frostbite (3rd or 4th degree) quickly become thrombotic (<20 minutes) with mottling or demarcation, however, the demarcation may be subtle at first and requires careful observation.

In the case that the tissues return fully to a normal color and palpable pulses or Doppler digital signals are present, the patient may not need any further intervention other than close observation (inpatient or daily visits in the clinic) and pain management.

If any question exists, an urgent triple-phase bone scan can support perfusion to the affected area.

Figure 4. Early evidence of demarcation and patchy thrombosis

Indications for Thrombolytics

Patient presenting with frozen tissue (severe frostbite, 3rd and/or 4th degree)

Absent or weak Doppler pulses following rewarming

Clinical exam consistent with severe frostbite

< 24 hours of warm ischemia time (time from rewarming)

Time matters significantly. For each hour after rewarming delaying the start of thrombolytics decreased salvage rates even by 28.1%.

With correct training after discussion with a burn center that does a lot of frostbite care, thrombolytics can be safely started at the outside hospital prior to transfer to the center.

Frostbite Thrombolytic Protocol

Examine for any associated injuries or illnesses. If any question of injury the patient will require a head, chest, and abdominal CT to rule out any sources of bleeding.

The dosing of the thrombolytic requires an actual weight and while infusing the thrombolytic requires ICU status and monitoring for 24 hours.

Following completion of the therapy, the patient will immediately be started on treatment dose Enoxaparin for 1-2 weeks.

Figure 5. Patient before and after receiving thrombolytics

Contraindications to the Thrombolytic Protocol

Absolute contraindications:

> 24 hours of warm ischemia time

Repeated freeze/thaw cycles

Concurrent or recent (within 1 month) intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage or trauma with active bleeding

Inability to consistently follow a neurologic exam (eg. intubated and sedated, significant dementia)

Severe uncontrollable hypertension

Relative contraindications:

History of GI bleed or stroke within 6 mo.

Recent intracranial or intraspinal surgery or serious head trauma within 3 months

Pregnancy

Figure 6. Clinical guide for the management of frostbite

Frostbite Take-Home Points

Rapid rewarming of frozen tissue in a circulating water bath is the preferred method of rewarming.

Patients that have undergone trauma in conjunction with the frostbite injury are not an absolute contraindication to receiving tPA.

Starting tPA at the outside hospital, prior to transport, results in significantly improved outcomes even compared to those that receive it at UCH.

Frostbite patients, regardless of whether or not they get thrombolytics, do better at a center that has experience and protocols to take care of frostbite.

Anne Lambert Wagner, MD, FACS

Associate Professor

University of Colorado

Medical Director

Burn & Frostbite Center at UC Health

How To Cite This Post…

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] King, P. Porras, N. (2021, Aug 16). TPA in Frostbite. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Lamber Wagner, A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/TPA-in-frostbite.

Other Posts You Might Enjoy

References

Cauchy E, Davis CB, Pasquier M, Meyer EF, Hackett PH. A New Proposal for Management of Severe Frostbite in the Austere Environment. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2016;27(1):92-99. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2015.11.014.

Cline D, Ma OJ, Meckler GD, et al. Cold Injuries. In: Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: a Comprehensive Study Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020:1333-1337.

Grayzel J, Wiley J. What’s New in Emergency Medicine. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on November 3, 2020.)

Lee J, Higgins MCSS. What Interventional Radiologists Need to Know About Managing Severe Frostbite: A Meta-Analysis of Thrombolytic Therapy. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020;214(4):930-937. doi:10.2214/ajr.19.21592.

Pandey P, Vadlamudi R, Pradhan R, Pandey KR, Kumar A, Hackett P. Case Report: Severe Frostbite in Extreme Altitude Climbers—The Kathmandu Iloprost Experience. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2018;29(3):366-374. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2018.03.003.

Patel N, Srinivasa DR, Srinivasa RN, et al. Intra-arterial Thrombolysis for Extremity Frostbite Decreases Digital Amputation Rates and Hospital Length of Stay. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2017;40(12):1824-1831. doi:10.1007/s00270-017-1729-7.

Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An Open-Label Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Tissue Plasminogen Activator in Treatment of Severe Frostbite. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2005;59(6):1350-1355. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000195517.50778.2e.

Wagner A, Orman R. Frostbite, Asystole, Perfectionism, EQ, Middle Way, Flu. January 2019 - Frostbite - Frostbite, Asystole, Perfectionism, EQ, Middle Way, Flu | ERcast. https://www.hippoed.com/em/ercast/episode/frostbite/frostbite. Published 2019. Accessed November 3, 2020.

Zafren K, Crawford Mechem C. Frostbite: Emergency Care and Prevention. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on November 3, 2020.)