Written by: Adam Payne, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Julian Richardson, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: Matt O' Connor, MD

Expert Commentary

Thanks to Dr. Payne & Dr. Richardson for putting this together! I think this was well done, they’ve presented a concise overview of the safety and efficacy of droperidol.

There’s a lot of utility in droperidol. It’s great for nausea, migraines, and even as an adjunct for chronic pain. It’s also a very good choice for agitation. I use it most often for nausea. It’s been shown to be as effective as odansetron, and more effective than metoclopramide. Anecdotally, I find it works particularly well for gastroparesis and cannabinoid hyperemesis (with some low-concentration topical capsaicin cream), with less sedation than haloperidol. For migraines, it has been shown to be as effective as prochlorperazine. It works well for sedation in agitated patients as well; IV & IM it has a much faster onset than haloperidol, and so benzodiazepines typically do not have to be co-administered, reducing the level and duration of sedation and need for monitoring.

The black box warning significantly limited droperidol’s availability, such that many of our newer graduates have not had any first-hand clinical experience with the medication. If you’re not familiar with its use, don’t let the black box warning completely dissuade you. Subsequent studies looking at emergency department droperidol use have shown it to be safe, and that complications related to QT prolongation are rare in typical doses. As a rule of thumb, the dose of droperidol is about half of the dose of haloperidol for a given indication. For nausea, migraine, or other pain, I usually start with 0.625-2.5mg IV, twice that IM, and can repeat dosing if needed (my most common starting dose is 1.25mg IV). For agitation, usually 2.5-5mg IM, though up to 10mg IM has been shown likely to be safe. Although it is prudent to be cautious, I think the literature supports droperidol’s use at appropriate doses in otherwise healthy patients.

Matt O’Connor, MD

Emergency Medicine Physician

BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Payne, A. Richardson, J. (2021, Aug 30). Droperidol. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by O’Connor, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/droperidol

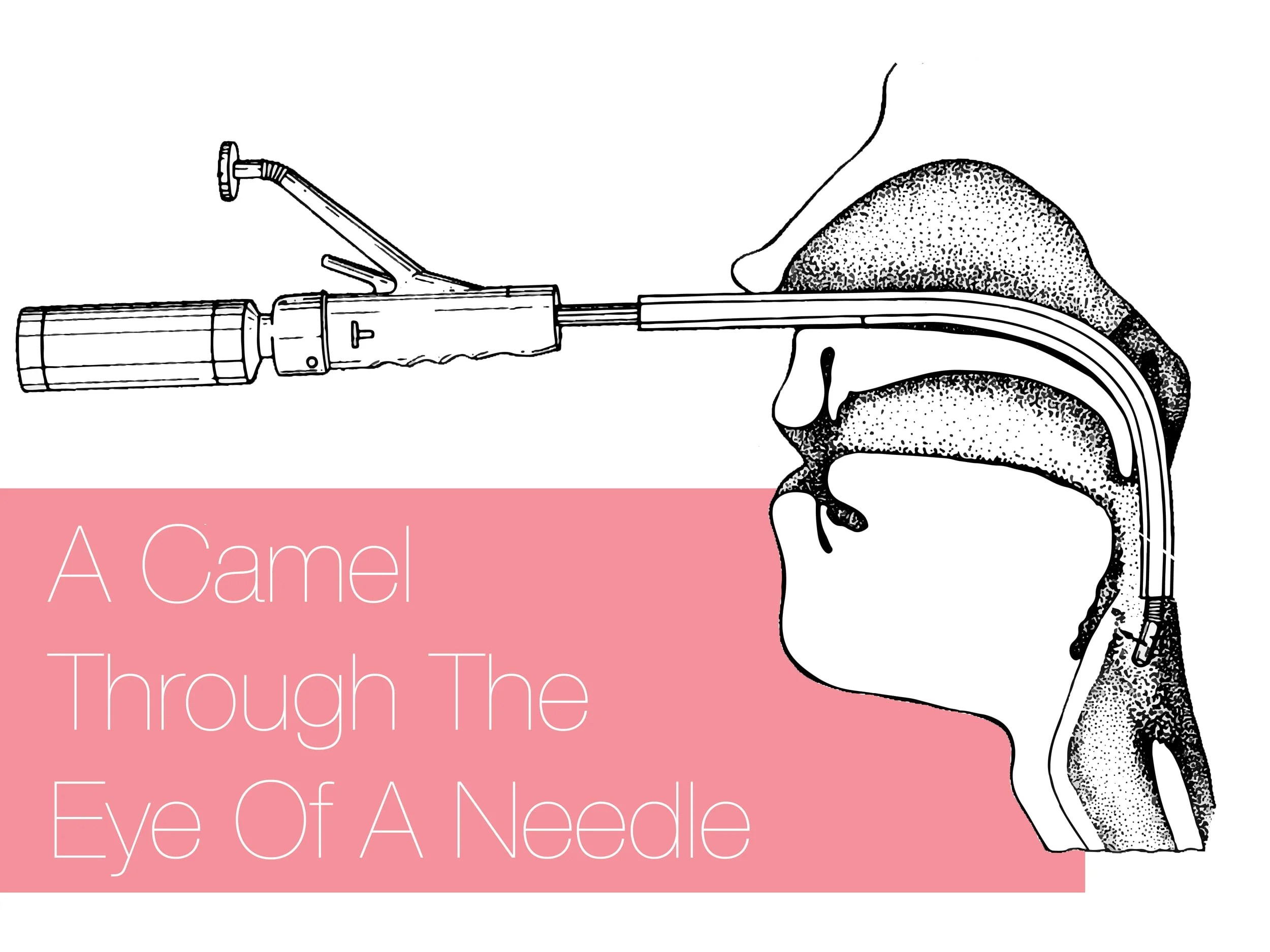

![Image from: Scott Weingart. Podcast 060 – On Human Bondage and the Art of the Chemical Takedown. EMCrit Blog. Published on November 13, 2011. Accessed on March 8th 2019. Available at [https://emcrit.org/emcrit/human-bondage-chemical-takedown/ ].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1567388477962-KRXLKHZYC5XNCEGD8VRQ/image-asset.jpeg)