Written by: Mike Conrardy, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Will LaPlant, MD (NUEM PGY-4) Expert commentary by: Seth Trueger, MD, MPH

I Want to be Sedated…

Mastering Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department

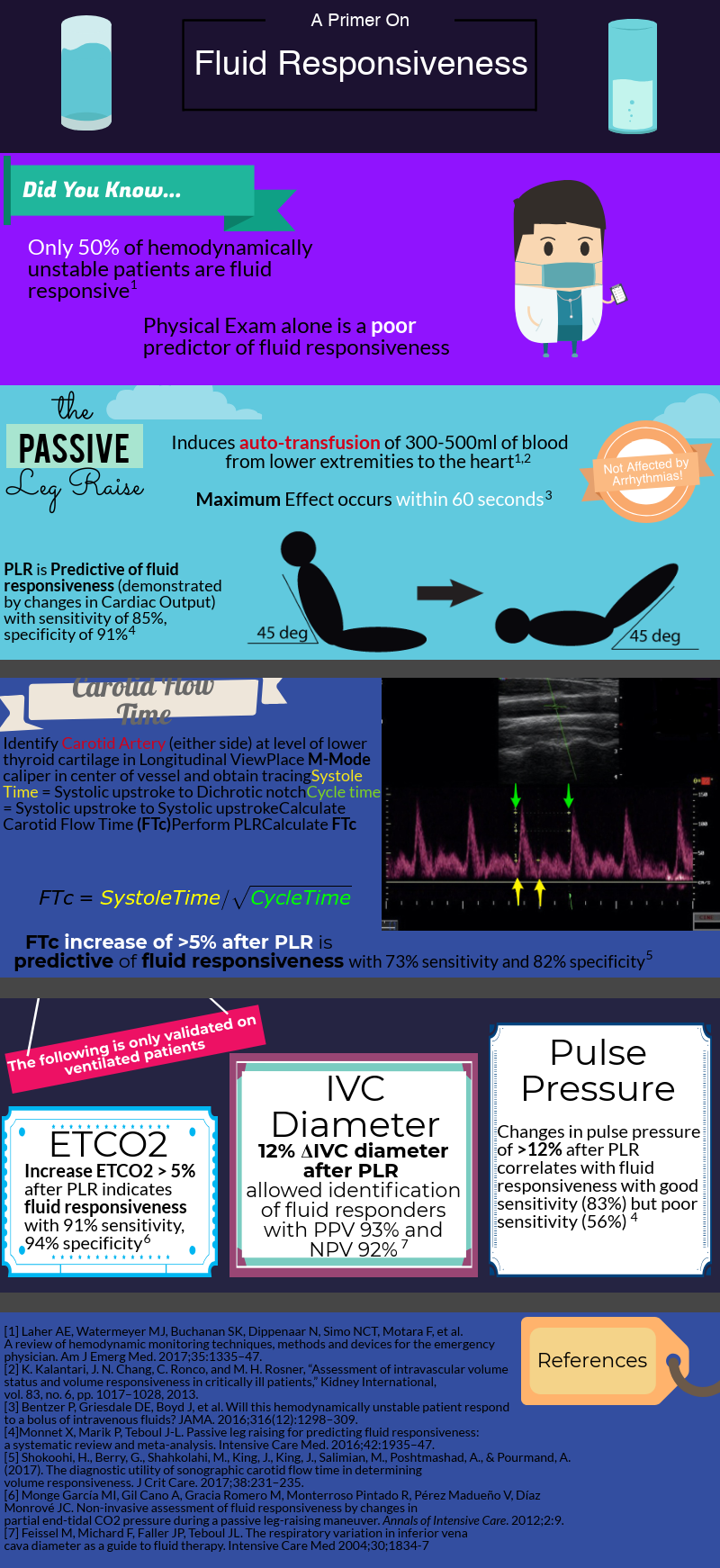

Procedural sedation, which is not called conscious sedation given the goal is to ensure the patient is not fully conscious, comes in a variety of flavors. Propofol, ketamine, or “ketofol” (the two used together) are typically preferred by emergency physicians, yet there are other options that may be more appropriate depending on the circumstances. In this article, we will provide a brief overview of the basics of procedural sedation, then dive deeper to provide more information about the specific agents that can be used for procedural sedation, including the pros and cons of each.

How many people are necessary to perform procedural sedation?

Generally it is recommended to have three personnel for procedural sedation (typically at least one doctor to perform the procedure and two other providers to provide sedation and monitor the patient), although using two providers (one doctor and one nurse) has been shown to have a similar complication rate.

What type of monitoring is necessary during the procedure?

Monitor vitals, telemetry, SpO2, EtCO2, and the patient’s level of sedation by physical exam. I prefer having EtCO2 if it is available, although remember EtCO2 can lead to false positives (e.g. suspected apnea when apnea is not present), but also provides earlier recognition of hypoventilation.

What other supplies should I have ready?

Oxygen by face mask has been shown to reduce likelihood of hypoxemic episodes. In addition to the above monitoring equipment, at the bedside you should have a bag-valve-mask, oral airway, nasal airway, suction, and intubation supplies ready in case they are needed. A good acronym for remembering all the supplies is SOAP ME: Suction, Oxygen, Airway equipment, Preoxygenation, Monitoring, Medications, ETCO2. As with most procedures, preparation is the most important step.

What are the most common complications of procedural sedation?

Aspiration (<2%), intubation (<2%), laryngospasm (<5%), nausea/vomiting (<5%), respiratory depression (10-20%), hypotension (10-20%), and emergence reactions if using ketamine (up to 20%).

What if my patient is pregnant?

Unfortunately, we have limited data on the safety of procedural sedation in pregnant patients. We do know that pregnant patients are more prone to hypoxemia, can be more difficult to intubate due to physiologic changes to the airway, and have a higher risk of aspiration when sedated after 16 weeks of pregnancy. Clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits of performing sedation in a pregnant patient, but if a procedure is emergent, delay is not a reasonable option. To reduce the risk of aspiration, utilize left lateral decubitus positioning and consider using pre-procedural metoclopramide and antacids.

Etomidate, propofol, and ketamine may all have an impact on brain development in pregnancy, but evidence in pregnancy is limited for all these medications and they have not been shown to be teratogenic. Propofol may be preferred given it is short acting and is used commonly for general anesthesia in pregnancy. Given that some benzodiazepines have been shown to be teratogenic, midazolam should not be used.

Prior to giving a sedating agent, is pretreatment necessary?

It is not necessary, but using ondansetron or another antiemetic prior to sedation may reduce vomiting and aspiration (and is at least generally safe and uncomplicated). Midazolam may also useful in conjunction with ketamine to reduce some of the post-sedation side effects, i.e. agitation and emergence reactions, although increases the risk of respiratory depression. More specifics are described below.

After sedation, when can a patient be discharged?

Once a patient is back to their neuromuscular and cognitive baseline, typically 30 minutes after the procedure, they can go home. Our practice is to PO trial a patient prior to discharge and ideally have them go home with a friend or family member who can monitor them at home for a few hours.

Agents:

Propofol:

Onset/Duration: Onset of ~40 seconds, duration of ~5 min.

Dose: 0.5 – 1 mg/kg loading dose followed by 0.5 mg/kg doses every 3-5 min or 20mg pushes every 1-2 mins PRN.

Pros: Short-acting sedative/amnestic, easy to redose, near immediate effect, decreased muscle tone for orthopedic procedures.

Cons: No analgesia, has pain on injection, can cause hypotension and respiratory depression.

Special notes:

Use a larger vein, such as in the antecubital fossa.

Recommended to pretreat with opioid (fentanyl, typically 50-100mcg) or ketamine for procedural pain. The downside of opioid pretreatment is greater risk of respiratory depression.

Injection pain can be reduced with intravenous 1% lidocaine mixed with propofol or prior to injecting propofol while occluding the vein. The dose is of lidocaine is 0.5mg/kg or approximately 3-4cc of 1% lidocaine.

Reduce the mg/kg dose in elderly and use lean body weight (calculator) in obese patients. No change is required in patients with impaired liver or kidney function.

Ketamine:

Onset/Duration: Onset of 30 seconds to 1 minute when given IV, duration of 10-20 min.

Dose: When used alone, dose is 1-2mg/kg given over 1-2 min followed by 0.5 mg/kg doses every 5-10 min PRN.

Pros: Dissociative sedative/analgesic with minimal respiratory depression, no impairment of protective airway reflexes, and no hypotension.

Cons: Ketamine can cause emergence reactions or post-sedation agitation (up to 20%), laryngospasm, nausea/vomiting, hypersalivation, tachycardia, and may increase ICP/IOP.

Special Notes:

Midazolam 0.05 mg/kg (2-4mg typically) immediately prior to ketamine can reduce rates of emergence reactions although increases rates of respiratory depression.

Avoid in patients with psychotic disorders.

Recommended for patients who may have a potentially difficult airway because there is less risk for respiratory depression.

This is the first-line medication for children above 3 months of its impeccable airway safety and provides both sedation and analgesia as a single agent (no need for opioids).

Combined Ketamine and Propofol, AKA “Ketofol”:

Onset/Duration: Same as above for each medication.

Dose: 0.5 mg/kg of each medication followed by propofol 0.5 mg/kg doses every 3-5 min or 20 mg pushes every 1-2 mins prn. Of note, individual provider choice of dose for each medication varies widely.

Pros: Potential benefit is ability to use lower doses of both ketamine and propofol with potentially lower risk of adverse events such as hypotension, respiratory depression, emesis, emergence reactions.

Cons: May reduce side effects of each medication individually, yet now dealing with the side effects of two medications rather than one alone.

Special notes:

Research on ketofol is mixed. Systematic reviews have shown that it causes fewer events of respiratory depression and hypotension/bradycardia, yet these events were mostly transient and clinically insignificant. Overall, ketofol has not been shown to reduce clinically significant adverse events or to prolong procedural duration.

Etomidate:

Onset/Duration: Near immediate onset when given IV, duration of 5-15 min.

Dose: 0.1-0.15 mg/kg given over 30-60 seconds, redose every 3-5 min.

Pros: Easy to dose, minimal hemodynamic effect.

Cons: No analgesia, myoclonus (up to 80%), respiratory depression (10%), nausea/vomiting, pain with injection, and potential for adrenal insufficiency.

Special Notes:

Recommended to pretreat with opioid (fentanyl, typically 50-100mcg) for procedural pain. The downside of opioid pretreatment is greater risk of respiratory depression.

In rare cases of severe myoclonus, treat with 1-2 mg IV midazolam every minute until resolved. Some providers pretreat with 0.015 mg/kg etomidate to prevent myoclonus.

Dose must be reduced for patients who are elderly or have renal/hepatic dysfunction.

Not recommended for orthopedic procedures given the frequency of myoclonus.

Midazolam (requires opioid co-administration):

Onset/Duration: Onset of 2-5 min, duration of 30-60 min.

Dose: 0.02-0.03 mg/kg or 0.5-1 mg doses IV every 2-5 min prn, typically not exceeding 5 mg total.

Pros: Provides anxiolysis and amnesia.

Cons: Not as effective for true procedural sedation as shorter acting medications, no analgesia, higher risk of respiratory depression when combined with fentanyl compared to other medications.

Special Notes:

When combining with fentanyl for pain/sedation, give midazolam doses as above first until the desired anxiolysis is achieved, typically 1-2 doses, then give 0.5 mcg/kg doses of fentanyl every 2 min PRN, carefully titrated to effect, with maximum dose of 5 mcg/kg or approximately 250 mcg.

Prolonged sedation is high risk in patients who are elderly, obese, or have hepatic/renal dysfunction.

Use for anxiolysis rather than for true procedural sedation.

Barbiturates (Methohexital):

Onset/Duration: Immediate onset, duration of < 10 min.

Dose: 0.75-1 mg/kg followed by 0.5 mg/kg doses IV every 2 min prn.

Pros: Fast onset, short duration sedation.

Cons: No analgesia, causes hypotension/tachycardia, can precipitate seizures.

Special Notes:

You are probably never going to use this drug unless you are in a very resource limited setting, but you might as well know it is an option.

Dexmedetomidine:

Onset/Duration: Onset of 5-10 min, duration of 60-120 min.

Dose: Not well studied for procedural sedation, options are intranasal 2-3 mcg/kg or bolus of 0.5-1.0 mcg/kg over 10 min followed by infusion of 0.2-0.7 mcg/kg/hr.

Pros: Preserved muscle tone and respiration, much like natural sleep, provides some analgesia.

Cons: Potentially unpredictable effect, not well studied, risk of hypotension/bradycardia, longer acting.

Special Notes:

Delayed time to onset may limit application in the ED

Dexmedetomidine is just not ready for primetime yet, but worth further investigation.

Nitrous oxide:

Onset/Duration: Immediate onset, off within seconds.

Dose: 30-50% mixture with 30% oxygen.

Pros: Provides analgesia, anxiolysis, and sedation all in one.

Cons: Not typically available in emergency departments, needs scavenging system.

Special Notes:

Have been trying for years to get this constantly vented into all our patient rooms, but still no luck with our administration.

Summary Points:

Propofol, ketamine, ketofol, and etomidate are our typical first-line medications in the emergency department for procedural sedation.

Ketamine is preferred for kids.

In adults, propofol or ketofol is best for hemodynamically stable adults requiring procedural sedation, particularly for joint reductions because it does not cause myoclonus and is easy to titrate.

Etomidate provides greater hemodynamic stability and is best for cardioversion or procedures in patients with hemodynamic compromise, but the downside is myoclonus which may reduce procedural success.

Ketamine alone is best in patients with a difficult airway or at high risk for respiratory compromise because it does not cause respiratory depression.

Use what you are most comfortable with, and remember that adequate preparation is key.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for the excellent and concise review. It’s been interesting to see procedural sedation practices change over the course of my training and career, as newer safe and easy options (propofol and ketamine) gained rapid popularity but have been challenged by drug shortages and well-publicized celebrity tragedies. Here is my typical practice, which is certainly not the only correct way but my strong preference:

A few factors on when to think about procedural sedation:

-Any painful procedure, particularly for potential for longer duration. This includes incision and drainage (especially Bartholin’s) and disimpaction. I’ve gotten some odd looks for suggesting it but it works out better for everyone involved.

-Consultant’s procedures, particularly big traumatic injuries which look nasty and like they need to be fixed. It’s easy to forget how terrible it is for the patient.

When I think about avoiding:

-medically complex patients

-difficult airways

-procedures that can wait

-procedures with low likelihood of success even under the best circumstances. If they need to go to the OR no matter what, that might be the best place to start.

My one exception are situations that are currently painful and need to be fixed now and can be fixed quickly, e.g. dislocated ankles. The likelihood of success with 100mcg of fentanyl within seconds to resolve a huge amount of pain now is exceedingly favorable.

The worst situation is trying to avoid procedural sedation with “just some morphine and maybe a little lorazepam” which quickly devolves into “a little more morphine” and “hmm maybe another dose of lorazepam.” Now it’s a procedural sedation that is both ineffective and unsafe.

My general process:

First I print out a checklist I made with the following preparation steps (details below):

RSI box (succinylcholine)

VL

airway cart (LMA, PEEP valve, DL gear)

nasal ETCO2 (plus ETT adapter)

4mg ondansetron now

bottle ketamine

bottle propofol

room ready (including suction, bag, anything required for the procedure)

Department ready?

Am I ready?

Procedure plan

Post-procedure planning (sling, splint)

The general principle is to set up at least as much as if I were performing RSI. A lot of this may seem like over-preparation, but the more I prepare, the luckier I get. Here is some more detail on each item:

RSI box (succinylcholine)

2 main purposes for the RSI box. First, if things go south, I will be intubating the patient, and need the medications to do so (i.e. NMBA). Second, if I am using ketamine, there is a small but nontrivial chance of laryngospasm, and of jaw thrust and bagging do not fix it, the patient needs NMBA. This is not a time to debate roc vs sux, so I always have sux in the room (even if roc isn’t slower when dosed appropriately at ≥1.2mg/kg, I don’t want to have to argue about it at the RCA). The easiest way for me to get these medications in the room is grabbing our RSI box, but this will depend on your department; simply grabbing a vial of sux with 1.5mg/kg is sufficient.

VL

If things go south, this is not the time for the intern to practice their DL. I always have the hyperangulated VL ready to go at the head of the bed, with a combo Mac VL/DL blade and a traditional Mac DL as backup, with stylets loaded with tubes ready to go.

Airway cart

We have nicely built airway carts with everything I need for bagging, difficult bagging, and difficult intubation. Primarily, what I want is gear for bagging, i.e. LMA and PEEP valve. All the usual backup is here as well (oral/nasal airways, bougie, cric gear).

Nasal ETCO2 (and ETT adapter)

The literature on end tidal in procedural sedation is interesting but I think generally answers a different question than the one I care about. I don’t look for qualitative changes in waveforms or quantitative changes in ETCO2 to predict hypoventilation; rather, it is the quickest and easiest way to see if the patient is breathing. No staring at their chest hoping to see chest rise. Simply look at the monitor: either there is a waveform and they are breathing, or there is not and they are not. It’s like a sedative for me, similar to supervising an intern using VL instead of DL: it makes the procedure much less stressful for me.

Additionally, by using ETCO2, it is now safe to provide supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula or reservoir facemask so if things go south, there is a much wider safety margin (i.e. the patient is preoxygenated for intubation).

4mg ondansetron now

As discussed above, it might help, it may not, and it’s safe and easy.

bottle Ketamine

bottle Propofol

I’ll discuss my medication strategies below, but the bottom line is I like to have multiple 100s of mg of each medication ready for each patient, because when I need to redose, it can be needed in a very short time.

Room ready

Other equipment I make sure is ready: suction, bag for mask ventilation. Other items like do I need vaseline gauze for splinting over an abrasion?

Is the Department ready?

Was an 80 year old with abdominal pain just roomed? Should I lay eyes on them and make a quick decision about an obvious CT? Is there a hospitalist hanging around who I can tell about another patient to send upstairs before I get stuck in a sedation for 45 minutes? Should I discharge anyone?

Am I ready?

Do I need to go to the bathroom? Has it been hours before I’ve had any calories?

Procedure plan

I always make sure to have a clear plan for the procedure—not just the sedation—well before we start. Who is doing what? What technique are we using? What are backup plans? Of course these questions apply to the sedation as well.

If a non-EM physicians is performing the procedure (e.g. ortho, or gen surg pulling a tunneled line) I try to make sure that they understand my definition of “ready” is not the same as in the OR, and I make sure they are ready to start the actual procedure as soon as the meds are working. This is not a judgment in any way; rather, the ER simply isn’t the OR.

Post-procedure planning

Few things are more frustrating than getting a difficult shoulder reduced only to have it slip out while someone is hunting down the sling I forget to get beforehand, that I knew I would need (see also: ordering post-intubation meds with RSI meds in an intubation). Obviously if something needs to be splinted we need the gear and whoever is doing the splint. And, if there are abrasions going under the splint, petroleum gauze, etc.

Medication choices

I typically choose between ketamine and propofol on a spectrum.

Factors on the propofol side: young, healthy, BP/respiratory reserve, shorter procedure, ortho procedure (propofol is much better at loosening up patients, plus these often end quickly).

Factors on the ketamine side: older, more comorbidities, less respiratory reserve, longer procedures, non-reduction procedures, more protractedly-painful procedures (e.g. I&D).

Obviously these are not absolutes and I tend to plan on using ketofol quite a bit. I usually have enough cognitive space and hands available to dose them separately (generally 0.5mg/kg ketamine first, then 0.5mg/kg propofol as needed) but in more constricted settings I will mix 1:1 if I don’t have the bandwidth.

I will say I have been tending to more and more ketamine-only sedations. Usually I start with the intention of using ketamine-first ketofol, particularly if the patient needs to be loosened up for a reduction, but I am continually surprised by how little I end up needing the propofol.

As noted above, for solo propofol, I pretreat with fentanyl as propofol is not inherently analgesic.

I appreciate the debate about midazolam for pretreatment for ketamine, but the rates of substantial post-sedation agitation are low enough that I simply treat that when it happens, as not all but most ketamine respiratory depression only happens with co-administered sedatives.

Other than lack of availability of other options, there is no reason to use fentanyl/midaz anymore.

Lastly, I’ve stopped using etomidate. The rate of myoclonus is simply too high. Myoclonus easily defeats the reduction, and even for cardioversion, it makes checking the rhythm, getting an ECG, monitoring the sat, etc. very difficult. Ultimately, it’s just a headache we don’t need, particularly as we have so many other safe and effective agents.

As I said above, these are more my style preferences than the only absolutely correct choices, and I am always happy to at least discuss adapt to the circumstances including others’ preferences (or trying something different so the residents can gain experience with different techniques).

Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, FACEP

Assistant Professor

Northwestern Emergency Medicine

Citations

Brown TB, Lovato LM, Parker D. Procedural sedation in the acute care setting. Am Fam Physician 2005; 71:85.

Swanson ER, Seaberg DC, Mathias S. The use of propofol for sedation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 1996; 3:234.

Miner JR, Burton JH. Clinical practice advisory: Emergency department procedural sedation with propofol. Ann Emerg Med 2007; 50:182.

Euasobhon P, Dej‐arkom S, Siriussawakul A, Muangman S, Sriraj W, Pattanittum P, Lumbiganon P. Lidocaine for reducing propofol‐induced pain on induction of anaesthesia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD007874. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007874.pub2.

Messenger DW, Murray HE, Dungey PE, et al. Subdissociative-dose ketamine versus fentanyl for analgesia during propofol procedural sedation: a randomized clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med 2008; 15:877.

Strayer RJ, Nelson LS. Adverse events associated with ketamine for procedural sedation in adults. Am J Emerg Med 2008; 26:985.

Adnolfatto G et al. Ketamine-Propofol Combination (Ketofol) versus propofol alone for Emergency Department Procedural Sedation and Analgesia: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012;59(6):504-512.e2

Miner JR et al. Randomized, Double-Blinded, Clinical Trial of Propofol, 1:1 Propofol/Ketamine, and 4:1 Propofol/Ketamine for Deep Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2015;65(5):479-488.e2

Yan JW, McLeod SL, Iansavitchene A. Ketamine-Propofol Versus Propofol Alone for Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22:1003.

Miner JR, Danahy M, Moch A, Biros M. Randomized clinical trial of etomidate versus propofol for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007; 49:15.

Falk J, Zed PJ. Etomidate for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38:1272.

Sacchetti A, Senula G, Strickland J, Dubin R. Procedural sedation in the community emergency department: initial results of the ProSCED registry. Acad Emerg Med 2007; 14:41.

Keim SM, Erstad BL, Sakles JC, Davis V. Etomidate for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Pharmacotherapy 2002; 22:586.

Hüter L, Schreiber T, Gugel M, Schwarzkopf K. Low-dose intravenous midazolam reduces etomidate-induced myoclonus: a prospective, randomized study in patients undergoing elective cardioversion. Anesth Analg 2007; 105:1298.

Horn E, Nesbit SA. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of sedatives and analgesics. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2004; 14:247.

Bahn EL, Holt KR. Procedural sedation and analgesia: a review and new concepts. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2005; 23:503.

Frank RL. Procedural sedation in adults outside the operating room. Wolfson AB, and Grayzel J (Ed.) UpToDate (2018).

Hsu DC and Cravero JP Pharmacologic agents for pediatric procedural sedation outside of the operating room. Stack AM and Randolph AG (Ed.) UpToDate (2018).

G. Haeseler, M. Störmer, J. Bufler, R. Dengler, H. Hecker, S. Piepenbrock, et al. Propofol blocks human skeletal muscle sodium channels in a voltage-dependent manner. Anesth Analg, 92 (2001), pp. 1192-1198

J. Ingrande, H. J. M. Lemmens; Dose adjustment of anaesthetics in the morbidly obese, BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia, Volume 105, Issue suppl_1, 1 December 2010, Pages i16–i23.

Neuman G and Koren G. Safety of Procedural Sedation in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. February 2013, pages 168-173.

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Conrardy M, LaPlant W. (2019, Nov 11). Procedural Sedation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Trueger S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/procedural-sedation.

![Figure 1: Sonographic view of trachea showing air-mucosa interface with posterior reverberation and shadowing artifact. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626234251-VL5QSV3R6S608OO7J8OI/1.+Figure+1+-+Trachea.png)

![Figure 2: Clip demonstrating the bullet sign: a single air-mucosa interface with increased posterior shadowing and artifact indicates the trachea has been intubated. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626261525-86AN0IKGCSGN5EHY11VN/image-asset.gif)

![Figure 3: Clip demonstrating the double tract sign: the appearance of a second air-mucosa interface with posterior artifact adjacent to the trachea indicates the esophagus has been intubated. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626372841-E4OFNNGZHEOI7ECDRIJP/3.+Figure+3+-+Double+Tract+Sign.gif)

![Figure 1: Bruising patterns that suggest child abuse. [6]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459114532-IVTA7KT3PX1J6DGC3U3L/Figure+1%3A+Patterns+of+Bruising)

![Figure 2: Forced immersion burn of buttocks with bilateral, symmetric leg involvement in a “stocking” pattern. [7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459322548-EFHGSFQ962QP9FU5DNJN/Figure+2%3A+Burn+patterns+that+suggest+non-accidental+trauma)

![Figure 3: Classic metaphyseal lesion. White arrows denote femoral metaphyseal separation and black arrow denotes a proximal tibial lesion or “bucket handle.” [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459580501-8461RMF0P9706GJW7XJU/Figure+3%3A+Fractures+of+NAT)

![Figure 4: Posterior and lateral rib fractures of differing ages indicative of NAT [4]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570460464292-4QFTGMDQAB64NQBSYD9N/Figure+4%3A++Rib+fractures+of+differing+ages+indicative+of+NAT)

![Figure 5: Fundus of child with AHT with too-numerous-to-count retinal hemorrhages indicated by the black arrows. [8] The white arrow indicates small pre-retinal hemorrhages. The white arrowhead denotes hemorrhage extending into the peripheral retina…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570460641270-3V7M52RMMV1QDMZ3PA1S/Figure+5%3A+Occular+manifestations)

![Figure 6: Elements of the Skeletal Survey. Although a full skeletal survey is currently the standard of care for patients with NAT, there are ongoing research efforts to tailor X-ray imaging more specifically to each patient. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570461092995-EBKSMB5DI0GTGXY0R75N/Figure+6%3A+Skeletal+surgery)

![Image from: Scott Weingart. Podcast 060 – On Human Bondage and the Art of the Chemical Takedown. EMCrit Blog. Published on November 13, 2011. Accessed on March 8th 2019. Available at [https://emcrit.org/emcrit/human-bondage-chemical-takedown/ ].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1567388477962-KRXLKHZYC5XNCEGD8VRQ/image-asset.jpeg)